This is the third in a series of ‘deep dives’ into the foundational rituals of the Ogdoadic tradition. As in earlier essays, everything in here is the fruit of my own work: it is entirely unofficial. It might help to read the essay on the Calyx, especially, prior to reading this one, as it is an essential part of the Setting of the Wards of Power. Practice of the Wards represents the student’s first step into ritual proper; like the Calyx, it is a deceptively simple ritual which repays practice and contemplation.

The ritual text of the Setting of the Wards of Power (hereafter ‘Wards’) can be read on the ORS website. It is, of course, also available in Denning & Phillips’s classic presentation of the rituals of the Aurum Solis. Any half-educated magician will notice its similarities with – and perhaps its differences from – the Golden Dawn’s pentagram ritual. We will come to these. I’ve appended some practical notes on ritual performance, culled from my own diaries, to the end of this post.

On visualisation and practice

Magical visualisation is a frequent stumbling block for beginners. Many occult groups instruct the student to undertake a battery of exercises, like maintaining the mental image of a red triangle or a green square for a period of time, in order to build up the faculty. I’ve used those exercises myself: they’re helpful in developing a skill often atrophied today, but they can also be immensely (and unnecessarily) boring. If such exercises are used, they should be alongside actual ritual performance, rather than for a period of months before doing any actual magic.

Why? Visualisation is not just about the use of mental muscle, but the opening of the subtle senses. The power being invoked ought to form a feedback loop to reinforce – or even change – the visualisation. This does not obviate the need for training and developing the skill, but it does speed it along. Because visualisations can be difficult to hold, it’s also tempting to conduct much of the ritual with eyes closed, but this risks making the ritual too much a mental abstraction and weakening its effect. Even if it is useful to reinforce the visualisation with closed eyes, opening them and affirming its reality in the sensible world is a good idea before moving on to the next phase. (This may initially make the ritual slower than it would otherwise be. The skill of standing between the worlds comes with time, but it comes.)

Needless to say this is not a hard and fast rule: there are very few of those in magic. There are also techniques – pathworking, meditation, some middle pillar-like exercises, empowerment of a ritual space – which work well with closed eyes and withdrawal from the senses. But in general, the embodied and physically present form of the ritual will provide a stronger foundation should it one day become necessary to perform it with no outward sign at all. It is always best to learn through doing.

But what does it do?

Like its Golden Dawn analogue, the Wards serves as an exorcism, balancing and sanctification of place. In their notes on the ritual, Denning & Phillips write:

“The purpose of the present ritual is to demarcate and prepare the area in which the magician is to work, with astral and Briatic defenses. The ritual consists of both banishing and invocation: the four Elements having been banished from the Circle in their naturally confused and impure state, the mighty spiritual forces ruling the Elements are invoked into symbolic egregores, to become Guardians of the Circle.”

Banishing and exorcism of the place of work are de rigueur in ritual magic: the grimoires offer a proliferation of exorcisms of both elements and places. As the equal emphasis on the invocatory part of the rite suggests, this is more than just a simple sweeping of the astral floor. Just like the Calyx, there are levels to this little rite which are not obvious at first glance, and only open out through practice and reflection; though it works on the working space as described, it also works on the magician herself. There are two obvious functions of the ritual according to the quotation above: cleansing the space and defending the magician. I would add a further two: establishing a rectified and perfect miniature cosmos, and by doing so balancing and empowering the magician. These two also make it, implicitly and subtly, a ritual introduction to theurgy.

Banishing, purity and spiritual fear

Perhaps it is worth spending a little time on a modern problem. A friend who runs a prominent occult shop mentions to me that the most frequent request they get at the counter is for a spell, or a ritual, or a guide on how to purify and cleanse; browsing the magical internet, similar questions about dangerous energy, astral parasites, or ever more elaborate forms of purification are very common. Fears about maleficent spirits or curses abound, as do hawkers of expensive bits of rock or pewter offering to rid you of them. This is not new – anti-curse magic is abundant in all historical periods – but it is a little alarming that it’s so prominent, sometimes to the exclusion of much else. We live in an anxious age, but even that doesn’t suffice to explain it.

A culture (or individual) with a hypertrophied sense of purity, and a deep fear of contamination – and which thinks of all interactions with the world and with other people as an opportunity for such contamination – is a very damaged one, prey to paranoia and obsession. Perhaps some of the emphasis laid on banishing in 20th century magical curricula is responsible for this, albeit dilutely and at some remove. Tacitly received ideas about a fallen world and personal sin might also be at play, and such received ideas are harder to break with emotionally and instinctively than many believe. Of course malicious magic exists – nor is it that rare – but this is a warning against an occult version of scrupulosity, once recognised as a serious spiritual disorder. (Phil Hine has written recently and perceptively about ‘astral hygiene’ in a similar context.)

The phrase quoted above, about the ‘naturally confused and impure state’ of the elements, should not be read as articulating a moral abhorrence of the sensual world. (Denning and Phillips are clear elsewhere in rejecting that kind of cosmic pessimism.) We might think of it as being closer to chemical rather than moral purity, or that the little universe that the magician constructs in the circle represents the perfected cosmos, free of the mutability and admixture in which we usually encounter the elements. I will have more to say on the symbolic cosmos below, and return to the question of ‘the fall’ and how to think about the material world in a later piece. Briefly, ideas about impurity or fallenness describe something obviously very common in human spiritual experience – suffering the flux and reflux of the sublunary world – but the primary key in which western seekers feel this is a useless and toxic blend of guilt and shame, or (through negation) a shallow hedonic antinomianism. Neither is useful for the magician. Magic, though it has its periods of abstraction and withdrawal, ought generally involve us more in the many wonders of the world, even while ceasing to be beholden to them.

A well-executed daily practice of the Wards, then, does have clear effects on the magician as well as the space in which it’s performed. Along with the other foundational practices, it strengthens the will and thus brings to awareness our habitual, programmed or automatic behaviours – and what lies behind them. It also strengthens the intuition, which means it combines well with a daily divinatory practice. Naturally, it is very useful as an all-purpose exorcism, whether in a place haunted by terrible events or simply somewhere stress and difficulty have left an imprint. It is safe and even beneficial to practice it where you sleep, and in my experience this means a richer dream life.

On the Magic Circle

The Wards bear the imprint of the Victorian occult revival, but the concept of the magic circle is far older. Scattered (and mostly ambiguous) examples of magic circles survive from the ancient world, but it is in the grimoires of medieval and early modern magic that they are most recognisable to us. A full examination of the history is beyond the scope of this essay, but there are two traits worth noticing in the older traditions. The first, and most obvious, is the stress laid on the protective function of the circle, e.g. in the preface to the English version of the Heptameron (1655): ‘they are certain fortresses to defend the operators safe from the evil Spirits.’ But the tradition also hints at why a circle is used by the magician, and these discussions present many useful avenues for deepening magical practice. The locus classicus is Agrippa, in his chapter on geometrical figures (II.xxiii):

A circle is called an infinite line in which there is no Terminus a quo, nor Terminus ad quem, whose beginning and end is in every point, whence also a circular motion is called infinite, not according to time, but according to place; hence a circular [form]1 being the largest and perfectest of all is judged to be the most fit for bindings and conjurations; Whence they who adjure evil spirits, are wont to environ themselves about with a circle.

1 – The translation here is more than usually haphazard; Agrippa’s Latin means essentially ‘the form of a circle is the best of all lineal figures’, thus my small emendation.

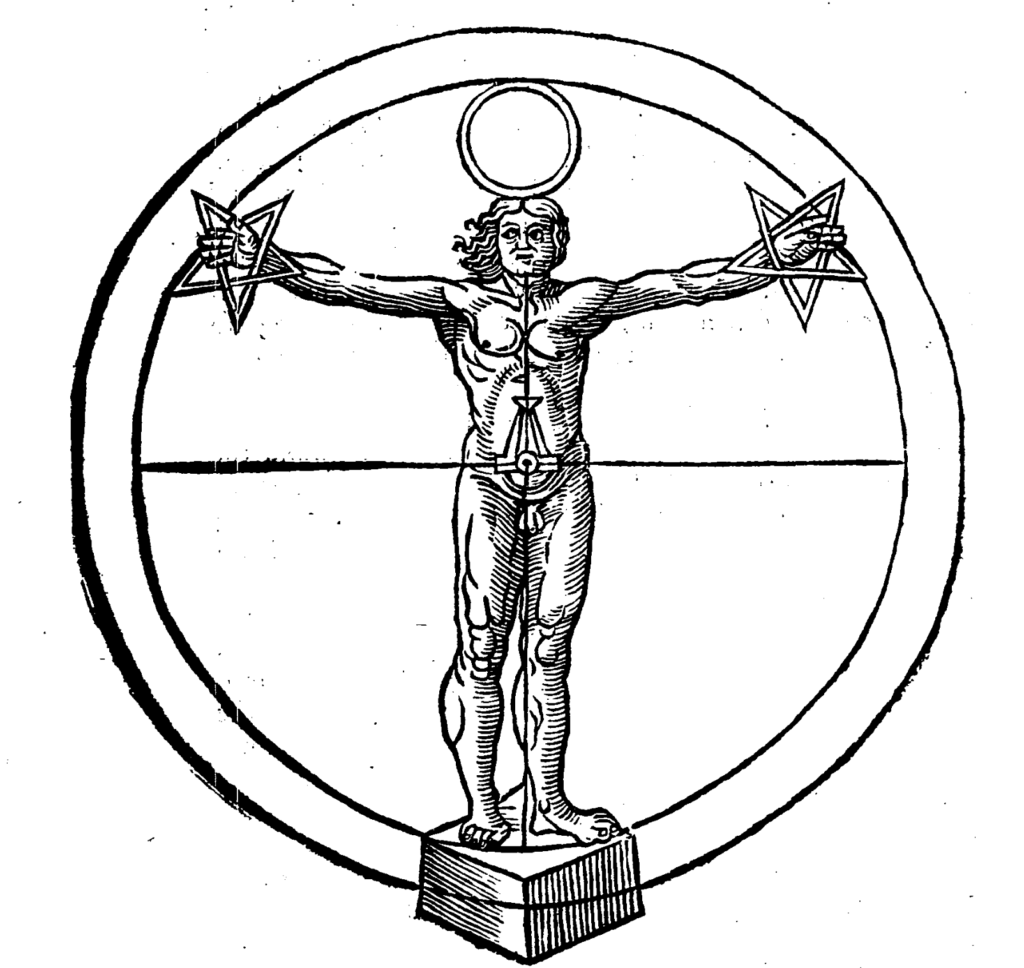

A scholar might detect distant echoes of Aristotle’s Physics in this passage, or perhaps the aphorisms of the medieval Book of 24 Philosophers. Most striking for magicians, though, is that Agrippa also goes on to discuss the pentagram as well as the significance of the quaternary, the ‘most firm receptacle of all Celestial powers’. This sequence of chapters is especially concerned with the resonances between microcosm and macrocosm, the secret signatures and sympathies by which magic operates. And it suggests one of the keys to the many designs for circles in the grimoire tradition, which combine the infinite symbol of the circle with the fourfold symbol of the material world – usually by cardinality of some kind, whether at quarters or cross-quarters. The circle for the infinite, the square or the cross for the material. That is, the circle itself is a miniature kosmos. (Ancient defenders of pagan theurgy also argued this about the circular design of temples: see Sallustius, Peri theon… § XV.)

Two quite distinct qualities of the practicing magician come out of the grimoire material on magical circles. Firstly, that he or she is powerful: amplified by standing inside a living symbol the magician can call up – or down – Agrippa’s ‘Celestial powers’. But, second, that he or she is vulnerable: that those powers may harm, obsess, derange as much as heal, transform or enlighten. The juxtaposition of these qualities reveals a truth: magical practice involves a risky opening of the self to the cosmos; the openness that makes us vulnerable is also the route through which power comes and spirits are called. One goal of magical training is to cultivate and direct this openness while learning to protect against its risks. But at its core is that openness and vulnerability: magic that risks nothing achieves nothing. The second power of the magician is to dare.

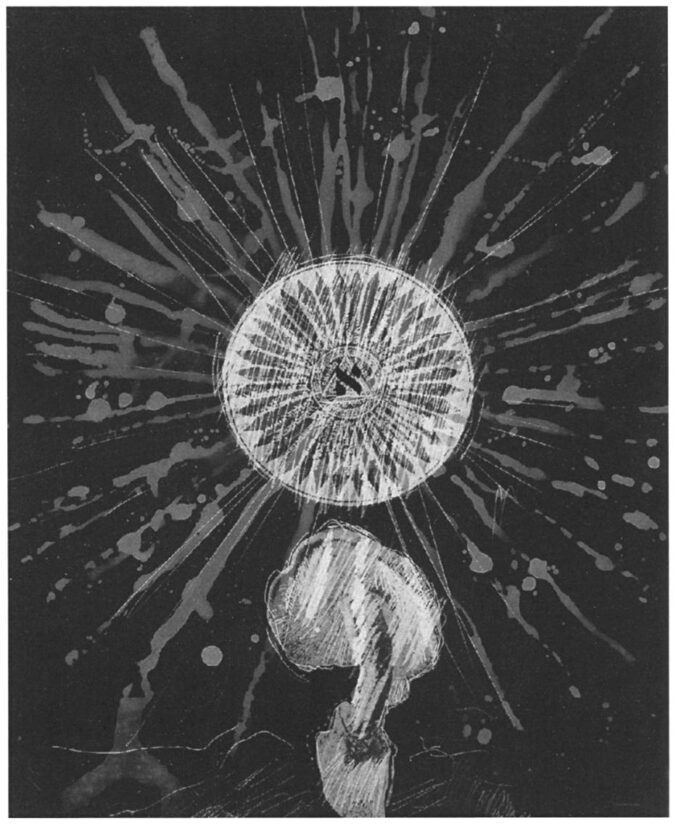

Agrippa is often a useful prompt for meditation, but is also a useful because Victorian occultists often turned to him when developing their grand and sometimes unwieldy magical syntheses. Much of the foundation material for modern ceremonial magic was drawn from Agrippa’s own early modern synthesis. Transmission of this kind is usually textual, but one might also speculate about the impact of the illustrations in De Occulta Philosophia. A few pages on from our quotation above, a reader will find a mysterious and evocative illustration in the chapter on the human body (II.xxvii), which combines the circle, the quaternary and a human being wielding pentagrams in both hands. Did this image linger in the minds of the eventual redactors of the Golden Dawn’s pentagram ritual, who must have stared at it, entranced, under the lamplight in the reading room at the British Museum?

Ritual Roots

Like the Golden Dawn’s pentagram ritual, the Wards maintains the defensive and symbolic aspects of the magic circle mentioned above, but adds to it techniques of mental concentration, visualisation and vocalisation. Whereas before the symbols and divine names may simply have been drawn on the floor, these rituals ‘activate’ them through the magician’s body, in a way very typical of late Victorian occultism and its 20th century descendants. (I’ve written about this before, and noted that in the earliest extant GD manuscripts these inner techniques are absent; whether they were passed mouth-to-ear or developed a little later I leave to the reader’s judgement.) The centrality of these techniques puts the rituals of the 20th century Aurum Solis and the Ogdoadic tradition firmly in the mainstream of post-Victorian revival magic – just like the Stella Matutina, the A∴A∴, initiatory Wicca and many others.

Is this, then, just the pentagram ritual with the serial numbers filed off, gussied-up in Greek drag? No: it draws influence from other sources, and includes significant changes to the structure and function of the ritual. For instance, the flinging of the pentagrams into the quarters suggests the influence of Crowley’s Star Ruby (first published 1913 but known to most magicians from 1929’s Magick in Theory and Practice.) Unlike many ceremonial magicians of their period, Denning and Phillips do not share the dislike for Crowley common among their peers; their mentions are rarely overt but are complimentary. Other influences on the implicit cosmology of the wards – explored below – allow us to date this recension, at least, to the mid-20th century. (This is not a suggestion that the predecessor occult societies to the Aurum Solis did not exist; I am fairly certain they did.)

That is what textual criticism tells us, what of magical experience? I have already indicated some of the rite’s beneficial effects, but it also feels subjectively distinct from the pentagram ritual. The two have a similar effect in clearing the space, of course. But the cosmogonic symbolism is stronger in the Wards: it is a ritual drama creating a symbolically complete universe in miniature, a form common to many diverse spiritual traditions. In particular the interplay between the body of the magician as the axis mundi, the medium through which magical work happens and link between above and below, is much more strongly emphasised in the Wards. Unlike the pentagram ritual, the Wards is not modular: the tradition uses other methods for elemental invocation. It does, however, teach a great deal of basic ritual structure and regular practice will help develop an intuitive sense of fitness about other rites. With every performance of the rite, the magician recreates his universe, stepping out of linear time into the circular time of ritual; it is a daily practice of rectification of the microcosm. This symbolic balancing invokes real powers, which act on both the magician and the space in which the rite is performed.

N.B.: When magicians talk of the symbolic we do not mean it in the sense common today, as the opposite of actual or real. In a tradition that stretches as far back as Iamblichus, symbols are living things, connected in secret bonds, and magic of all kinds depends on their use. For us, the world is alive with powers and connections, and much of the art of magic is learning how to use those symbols to connect to the forces they embody: the world is a great, living theophany. We might easily understand the pentagram or the circle as symbols, but in this sense so too are the colours, scents, stones and names used in magic. Ancient magicians sometimes called them συνθήματα, sunthemata. In modern magic there are also special symbols which connect the magician to the powers of a particular tradition. The Tessera, which sits on the altar of every Ogdoadic magician, is one such symbol.

The Wards as Cosmogonic Ritual

Let us think about the Wards as a cosmic drama. First the magician empowers and orients himself with the Calyx. The tracing of the circle of mist recalls the infinite pre-creation waters – the deep – common to ancient myths. The circle itself is, of course, a symbol of infinite potentiality. The Greek invocation that follows is of two ancient images generative cosmic potential, recalling Orphic myths and, implicitly, the White Goddess and Black God of the Ogdoadic tradition. Then, in each quarter, the pentagram is made and the divine name of each element called: like all creation myths, it begins with division and ordering of the infinite. Note that this moves counter-clockwise, and by its conclusion the magician has effectively traced a circled cross in the space – a figure uniting the circle and the quaternary, and a traditional symbol of the manifest world. By another Greek invocation he affirms his position as the link between the celestial and the material, the axis mundi. An invocation of the four rulers follows: the great powers disposing and ordering the material world, again affirming the quaternary. The creation accomplished, the magician reaffirms his relation to the divine and concludes the rite with the Calyx.

Other lenses can be fruitfully applied to this rite – Kabbalistic, Hermetic, or according to the House of Sacrifice formula. All complement each other. All of them inform my thinking about the cosmogonic aspects of the rite. It’s my intention in the following to offer – rather than everything possible to say on the matter – cues and readings which flow back into practice and deepen our appreciation of what’s happening in the work. While I offer these as fruits of my own practice with the rite, I would also suggest that practice must come first, to feed in to reflection and meditation, which feeds back into practice. There is a danger, when simply reading texts on magic, to become overwhelmed by details or to feel one has understood simply by reading. I hope these are spurs to deeper practice rather than arid intellectual completion.

The Calyx has already been examined in detail: here it opens the rite with the descent of spirit into matter, at the centre of the space. The still point of the turning world. It corresponds to the inspiring breath, Pneuma.

The Circle. (Principle: Sarx)

Little more needs to be said about the circle itself, the symbolism of which is covered above. Note that the circle is visualised as a wall of mist surrounding the magician. This is helpful because mist is a good analogy for the pliable, shifting medium through which magic works – called by some the ‘astral light’. Similar willed visual-imaginative work is done when learning the first stages of astral projection, emitting the nefesh as a mist from the solar plexus. Whatever this medium is called, it is responsive to human will, thought and consciousness; reflecting on this it is easy to see the clearing effect this rite might have on old habits and ideas the magician might be carrying around.

This mist is also the primordial waters of creation, and as in all creation myths the magician must divide the waters and give order to them. (The ancient historian Eudemus records a trace of Orphic myth that puts fog, along with time and desire, at the very start of the universe [fr. 150, qtd. Dam. Pr. III.163.19].) Kabbalistically-inclined magicians may feel here a distant echo of tsimtsum, the process of deliberate withdrawal of the godhead from itself to form the space of creation. There is a deep chain of symbolic linkages between the astral substance, the primordial waters, and the moon as governess of the tides and ruler of magic; these repay meditation.

A textual and ritual note: in the first edition of The Magical Philosophy, instruction is given to perform the circle widdershins, i.e., counter-clockwise. In later editions, the instruction is given instead to perform it clockwise. This reflects a change in the practice of the original A∴S∴. The magical effect is relatively slight, but having done it both ways, I find the widdershins turn helpful if the rite is preceding works of negation, diminution, banishment or disguise. (Denning and Phillips lay out the use of widdershins circumambulation in Paper XIV of Mysteria Magica.) As a complete daily ritual, though, I turn with the course of the sun, clockwise.

The First Invocation.

The magician vibrates two Greek phrases, which translate as ‘The Dove and the Waters’ and ‘The Serpent and the Egg’. These are two images of primordial generation. Though no instruction is given to visualise anything, the images are naturally suggestive, and can cause visuals of great intensity to rise in the mind, along with a sense of enormous latent power and potency. Both images allude strongly to Orphic creation myths, though their resonance is not purely Orphic – the spirit moving over the waters (or the void) is of course also a key part of the Genesis creation myth. The story of Phanes, or Protogonos – the first-born god emerging from the cosmic egg – is fairly familiar. Worth stressing here is that Protogonos is co-extensive with the entire cosmos: in one myth the universe blinks out of existence when he is swallowed by Zeus. M.L. West, for this reason, among others, compares him to the Vedic Prajāpati. (Many of the fragmentary details concerning Phanes-Protogonos are worth meditation: for instance, Damascius’s assertion that he is the first god knowable to human beings.) Through the use of these symbols, then, the tradition makes an explicit link to the Orphic mystery cults of antiquity, their later Neoplatonic interpreters, and their apparent central themes – especially resurrection and regeneration.

But the images also have specific resonance within the Ogdoadic tradition: they symbolise Leukothea and Melanotheos (lit. ‘the White Goddess’ and ‘the Dark God’), two of the deities central to Ogdoadic magic – the third, the Agathodaimon, appears slightly later in the ritual. They also suggest the two pillars, black and white, of the magical temple – between which the whole tapestry of the universe is woven. It is unsurprising that the parent deities are invoked at this stage of the rituald. It is not, however, a full and direct invocation of these powers.

A textual note: the images, though most are Orphic in ultimate derivation, are also clearly influenced by Robert Graves’s imaginative and idiosyncratic reconstruction of a ‘Pelasgian’ creation myth in his Greek Myths. Graves’s insistence that the ancient myths recorded fragments of a pre-Olympian cult of the Mother Goddess was, of course, hugely influential on the course of modern neopaganism, druidry and witchcraft. Such influence suggests that this particular recension of the Wards is unlikely to predate the mid-1950s. (It is possible, and quite likely, that other versions of this ritual preceded it.)

Although I am not particularly inclined to ipsosephy – the Greek equivalent of gematria – there are some resonances worth drawing out in these phrases: πέλεια, the dove, shares its value with ἱέρεια, meaning ‘priestess’. The Peleiades – doves – were also the sacred women of the mother goddess Dione at Dodona, the most ancient oracle in Greece. The total value of the second invocation sums to 12, suggesting the belt of the zodiac and the great cosmic serpent with which Melanotheos is associated.

The Wards (Principle: Dike)

In each quarter, proceeding anti-clockwise, the magician performs a complex gesture – first bringing his hands to form a triangle at his brow and visualising a blazing pentagram, then flinging this pentagram outward into the mist wall. The hands should spread, and the pentagram should be seen to grow before bursting in shimmering light in the mist. The spreading hands resemble the horns of a great stag, and so this gesture is called ‘Cervus’. At each point he vibrates the appropriate divine name: first that of spirit, and then that of the element as the pentagram is flung. This is the banishing part of the ritual proper, and thus its correspondence to the principle of justice, Dike.

This action is similar to the many exorcisms and prayers involving the four directions which recur across many religious traditions when marking out sacred space, or calling for protection – the common Jewish Shema before sleep, or St. Patrick’s Breastplate (sect. 8) spring to mind. The specific genealogy of the Wards is ultimately from Eliphas Lévi’s ‘Conjuration of the Four’, and – as suggested above – influenced by the pentagram ritual and Crowley’s Star Ruby. This ritual sequence banishes and fortifies the circle: it really is a sweeping of the astral floor. It is also the first part of the ritual structured by the quaternary, and thus symbolically addressed to the tangible world, rather than the circular or axial focus of preceding steps.

The symbolic lore of the pentagram is vast: it is the pre-eminent symbol of command and magical power. Here its aspects as a symbol of protection, the magus as microcosm, and the government of spirit over and through matter are especially relevant.

Some brief notes of interest: the assignment of the elements to the quarters is the same as in the Golden Dawn, and are taken from Ptolemy’s elemental attributions of the winds (in Ptol. Tetr. I.10). This attribution is shared by virtually all post-Victorian ceremonial magic, though other modes of assigning the elements to the quarters are possible: using zodiacal attributions, as in Agrippa, and placing fire in the east – sometimes still deployed in some planetary workings – and a Kabbalistic tradition stemming from Zohar II.24a, which has never to my knowledge been used by Western magicians.

The Cervus gesture should flow naturally with the rhythmic breath – it is also the first training in the projection of magical force. Notably the divine name of spirit – Athanatos or Ischuros – always precedes work with a particular element. (The two divine names for spirit is, I think, another legacy of the Golden Dawn – though like many Victorian innovations there is precedent for it in the wider tradition.)

Again, some brief examination of the divine formulae may be helpful. The two Spirit names, Athanatos and Ischuros mean respectively ‘undying’ and ‘mighty’. The name for Air, Selaê-Genetês, means ‘Father of Light’, an epithet of Apollo and appropriate for the rulership of the East. The name Theos for Fire means simply ‘God’, but ultimately derives from words related to a proto-Indo-European root meaning ‘shining’ (cf. the holy and formless shining fire of the Chaldaean Oracles). Pankrates, the name for Water, means ‘All-Powerful’ – a name especially appropriate for water’s power over physical and emotional life. Earth is assigned the name Kyrios, meaning ‘Lord’, mirroring the Hebrew assignation of Adonai to the same element; its value in isopsephy is 800, the value of the letter Omega (assigned to Saturn) and ὕπνος, hypnos, meaning sleep. There is food in all these names for meditation; in magical practice one ought to be entirely absorbed in the vibration of the name itself.

The Second Invocation

The circle banished and warded, the magician now stands in the centre of the place of working, upright and vibrates a Greek phrase translated as ‘Earth and the Blood of Heaven’. This is a moment of great symbolic importance in the ritual, for multiple reasons:

- Like the preceding invocation, it is delivered in the centre of the place of working, but the invocation calls on the Agathodaimon, the Ogdoadic deity attributed to Tiferet, the sun, and tutelary spirit for the magician’s theurgic development. As with the previous calling, the invocation is indirect but significant; the previous images of potential are followed now by the image of the descent of spirit into matter. The Agathodaimon is central to the magical work of the system, and this moment of daily contact with him is vital.

- The phrase continues the Orphic resonance of the ritual, recalling not only the ancient myth that human beings were created from the blood of the Titans (see West, p.165) but the initiatic phrase inscribed on the Orphic lamellae to be used as a password in the afterlife: Γης παις ειμί και ουρανού αστερόεντος – ‘I am a child of Earth and Starry Heaven…’ It is also worth noting that the ancients thought ichor a distinct substance from human blood.

- The axial moments of this ritual are of great interest – all those at which the magician is at the centre of the circle with his attention directed towards the divine. The literature here is vast and uneven, but closely linked to the cosmogonic aspect of the ritual. The fundamental practices of the tradition all involve work through the central column of the magician’s subtle body: the Calyx, these moments within the Wards, and all the formulae of the Clavis Rei Primae (similar to the Middle Pillar exercise) – and from this perspective it can be seen how they interlock and reinforce each other. When I have meditated on these moments, I have often seen the magician as a great cosmic tree, its roots deep in the darkness and its boughs entwined with stars. Significantly, one of the more advanced magical practices involves the assumption of the godform of the Agathodaimon as a serpent rising along the spinal column. (I will say more on this in my notes on the Clavis Rei Primae.)

- Students of the Kabbalah may find meditative resonances in the sequence of actions here: first the banishing of confused and chaotic elements, then the descent of the spirit – as with the Kings that were in Edom. This parallel is suggestive, not direct.

- The Agathodaimon is a solar deity, and it is striking that this allusion to him should precede the invocation of the elements in their pure and rectified form. The traditional Ogdoadic design of the Disk, the magical weapon of Earth, shows the colours of each element governed and illuminated by the rays of the sun.

The Four Regents (Principle: Eleos.)

Raising his arms to the Tau posture, palms down, the magician invokes the four Briatic Regents, or Archontes, governing the elements. These regents are equivalent to the Archangels in Hebrew working, i.e. extremely potent and pure facets of divine power. Denning and Phillips give specific elemental forms for visualisation, but also give notes for contemplation – the winds of the east and the spiritual aspiration they carry, the divine intoxication of the southern fires, and so on. (These are reproduced at the Citadel of Pharos website.) Getting all these layers in place at the same time is a serious exercise, and may at first take several cycles of breath to establish each figure fully: it is worth paying attention to whether one in particular is causing difficulty, as it may indicate special work is needed on something governed by that element.

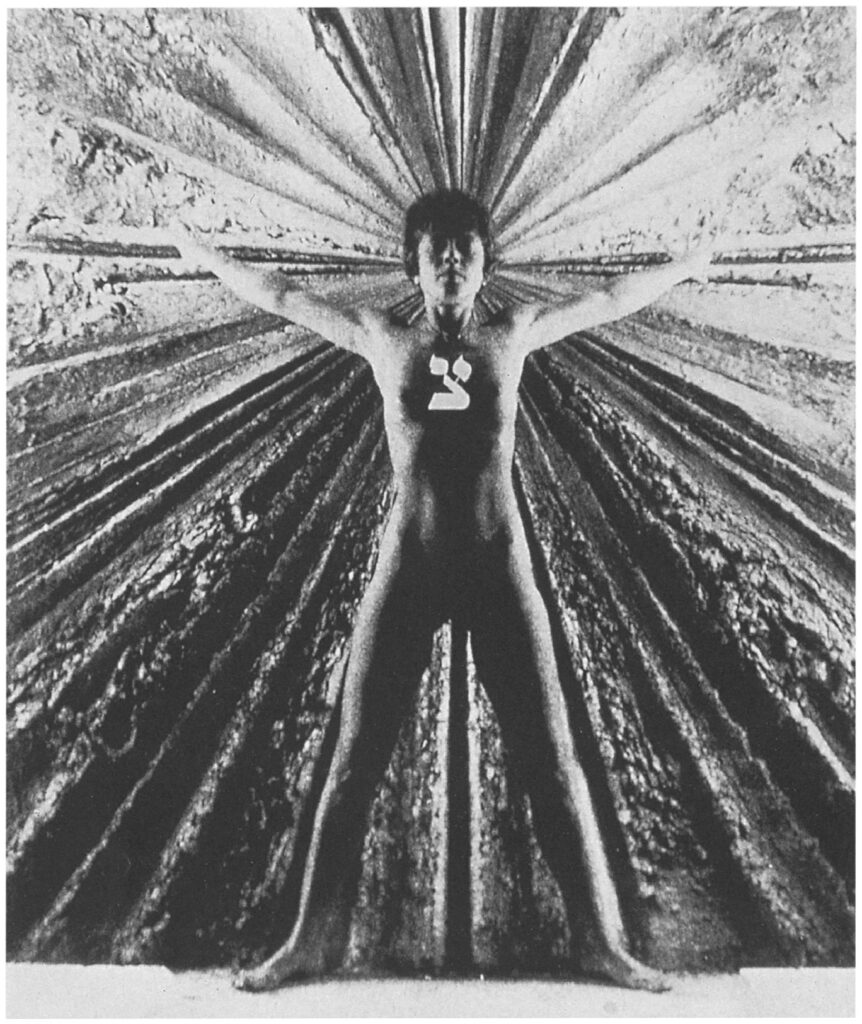

The Tau position occurs frequently in ritual: it is a sign governing the material world and the magus at its balancing point. Most frequently, with palms upturned, it is used in invocation of the highest powers – the divine name governing an operation, or as in the Ogdoadic formula The Magician, the divine spark above the head. Here, with palms down, it is a gesture of materialisation – manifesting the power of the elemental regents. It is worth noticing the way the orientation of the body changes by assuming the posture and changing the position of one’s hands. The body is the instrument through which we do magic: its movements matter.

The invocation of the four regents completes the symbolic cosmos: the four elements are present in their pure forms. In another sense, the four elements have been rectified: i.e., the ritual action symbolises one of the fundamental steps of magical development, mastery of the four elements – including their microcosmic reflections in the psyche. Many magical systems place this work in their first grade, but it is often neglected or scanted because it is unglamorous and requires honesty and self-examination. ‘Adepts’ who then proceed to blow their psyche apart are testament to its importance. No temple stands without a firm foundation. The Wards is an excellent basis and aid for this work; meditation and invocation of each of the regents in turn also helps.

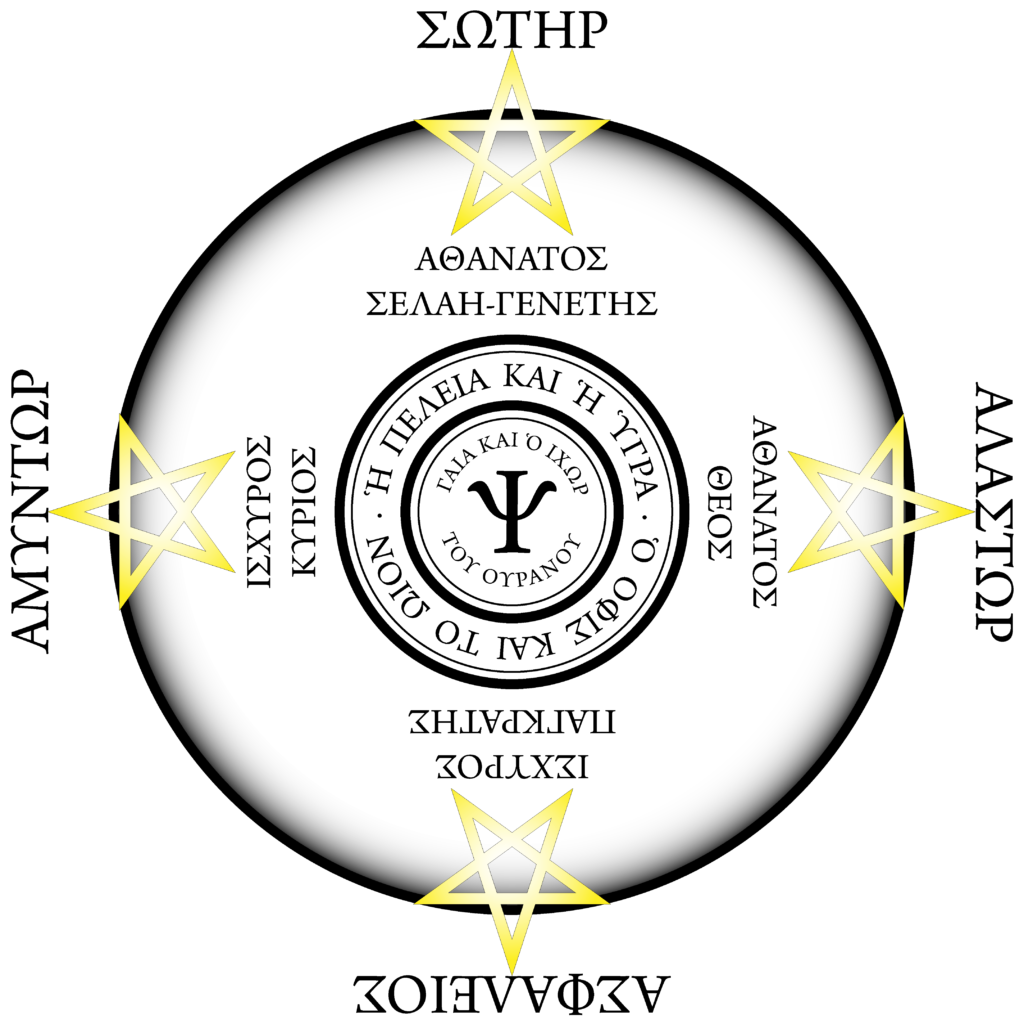

The names of the four regents are also titles or epithets: Soter, meaning ‘saviour’ applied to many gods but especially Dionysos and Zeus (and for theurgists, in its feminine variation, Hekate); Alastor, ‘avenger’, with varying shades of moral significance in antiquity; Asphaleios, ‘foundation’, an epithet of Poseidon understood as referring to him as giver of safety on the seas; Amyntor, ‘defender’, and note that the elemental weapon of earth is sometimes called the shield. Denning and Phillips refer to the forms they give for these four regents as symbolic egregores, i.e., general-purpose symbolic forms specifically pertaining to their rule over the elements. The symbols are very obvious, though it should be noted that the sickle held by Amyntor instances the strong connection between Saturn and Earth that runs through the system. It is my experience that continued use of these forms will individualise them to some degree. They should not be deliberately altered by the magician’s imagination, however. The reason for this is worth stressing: they are not just symbolic forms of the elemental kings, but they are specifically forms used by magicians within this tradition every time we perform this rite. It is one way of linking our individual work to the wider work and power of the tradition, or like following tracks already made for us. This is one reason behind the strict instruction sometimes given in early training not to change this-or-that specific part of a rite or programme. It’s an instruction usually worth heeding.

The rite concludes as it begins, at the centre of the place of working, as the magician centres himself on the divine spark through the Calyx, and the final principle of the House of Sacrifice: Kudos.

The Uses of the Wards

The two primary uses of the Wards have already been indicated: as a ritual that clears, sanctifies and prepares a space for magical work, and as an individual rite which – through daily repetition – contributes to the spiritual transformation of the magician. This latter effect is greatly enhanced by also practicing the Clavis Rei Primae, akin to the Middle Pillar exercise: all the foundational practices inform and reinforce each other. It is also the rite that the magician will most often perform to open more elaborate workings (one variation, The Setting of the Wards of Adamant, elaborates and makes explicit the symbol of the circled cross as a representation of the specific divine powers of the tradition.) It is easy to take for granted, but honed and mastered it can change a space very rapidly; appreciation of its hidden depths develop through practice.

I’ve suggested above that one of the effects of the Wards is an increase in self-awareness, and in particular awareness of habitual actions which have outlived their usefulness. This is one consequence of a more general fortification and charging of the magician’s subtle body. Daily invocation of the kings of the four elements will also likely work to transform the parts of the psyche under their rule – leading some practitioners to a difficult early confrontation with acquired habits, dogmas, or empty forms of life which no longer suit them. This work is all to the good, but it conceals a risk – delaying progress in the work for an endless cycle of self-analysis, or frequent sharp and ill-considered changes in direction. It is worth thinking of oneself with love – and remembering that you are offering all of yourself for transformation and irradiation by divine power, not only the parts you think already worthy. One method I suggest: delineate the natal chart as a key to psychic makeup, paying attention especially to elemental distribution. Construct the sigils of each of the four regents using the elemental presigilla and the kamea of Malkuth (all given in Mysteria Magica.) Continue the daily regimen as normal but time each ritual to begin in the appropriate elemental tide, dedicating a week to each, decorating the space appropriately and adding in a daily meditation on the element, its regent, and in particular its effect in one’s life. This is both a helpful exercise as well as a nice training in gathering appropriate correspondences and decoration for the working space.

This elemental practice of theurgy points us towards the development of the light-body. The next post in this series will examine the set of practices related to the subtle body: the charging and development of the centres of activity, and their centrality to this form of magic.

Appendix: some notes on practice

I thought it might be useful to add these very practical notes, which are culled from my own magical diaries, to supplement the instructions. They are, I think, useful principles for ritual work in general.

- Confidence and clarity of purpose is more important than perfect visualisation. Visualisation will come in time, as the magical senses open up. It may also come in different ways, including auditory phenomena, or a sense of something akin to pressure: I often experience the closing of the circle as a satisfying, almost audible clinking sound.

- Self-doubt is lethal. Relaxation and trust in oneself, the powers, and the efficacy of the ritual is essential. This is not a state that can be achieved by trying for it, or indeed by telling someone else to strive for it. Take the internal policeman off duty for the duration of the work. A period of ten minutes of meditation prior to the work can help induce this at first.

- As the pentagrams are flung rather than physically traced, it’s useful to build them up – and specifically their motion when flung – in the visual imagination. What does each phase of process look like? What does it feel like to have a symbol of power burning between your hands and then flinging it out to a quarter? Revisiting these questions with the experience of practice is helpful.

- The ritual should be led and timed through your breath, ideally neither rushed nor languorous. Allow your breath to guide you. It is worth walking through it several times using the rhythmic breath to ‘pin’ the visualisations to certain sequences of breathing.

- Vibration of the divine names should be treated as a kind of personal transubstantiation: you are taking the name into your body and activating it, becoming more like it. (See the previous essay on the Calyx for more on this idea.) Again, it may take some time at first to build up the technique. Experimentation with the vibratory exercises given by Regardie can help as well, although it is not necessary to import this technique into the rite itself.

- The Archontes – the four elemental guardians invoked at quarters – are not ciphers, but real and individual spiritual presences. They are not extensions of the individual will. Meditation on their forms, and seeking out experience of their elements in the world, will help strengthen the invocation.

- Stick at it. Self-punishment for missing a day here or there early on is counterproductive. (But if you are inclined to self-punish in this way, or drawn to demanding structures which provide you an opportunity for self-punishment, you might find regular practice forces you to confront that.)

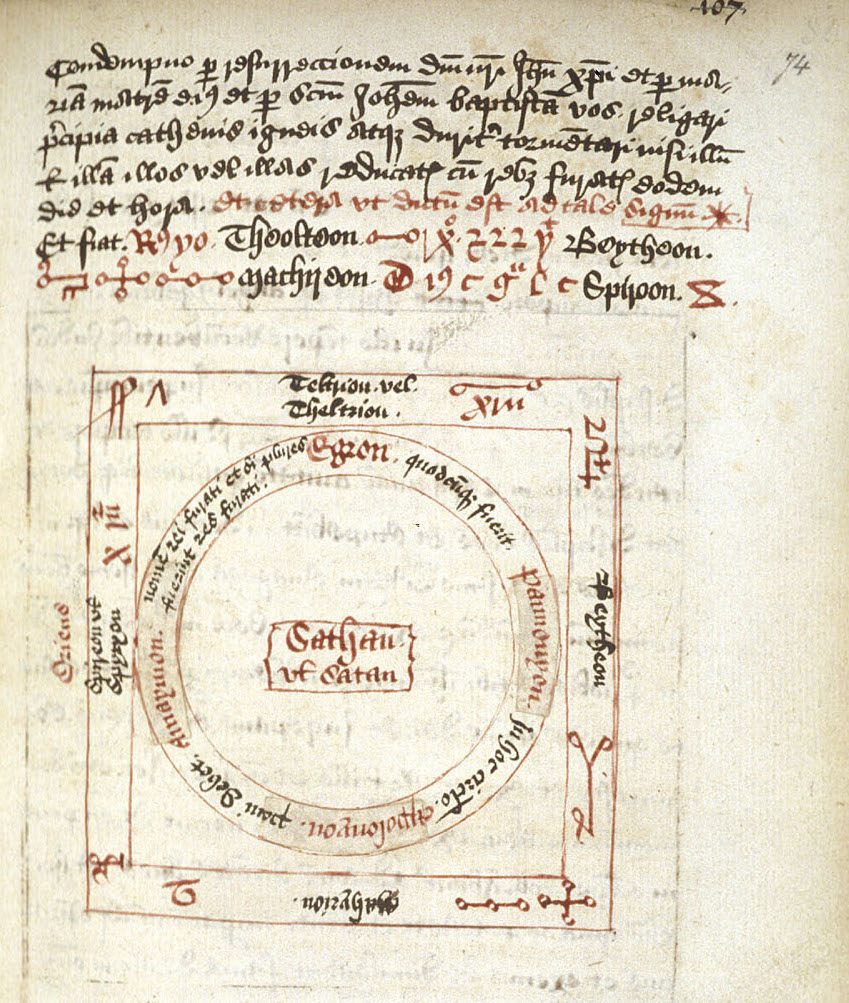

- In memorising rituals, I often find it helpful to draw or paint diagrams, which lay out the rite schematically; these figures can even sometimes become mandala-like themselves. They might be made with great and colourful elaboration and careful calligraphy, or they may tend to the more schematic. Though I would never share a photograph of my personal grimoire, this digital diagram suggests what the more functional version might look like. The letter Psi in the centre represents the magician with arms upraised, ready to receive the divine influence, as in the Calyx.