‘From the Gates of Night I have come to the sill of day,

I have passed the Brazen Door. She has grasped my hand–

The Goddess, my Queen–

and has bidden me still seek truth on the inward road

of knowledge, while opinion roams the world.’

–– opening invocation of ‘The Magician’, after Parmenides.

A friend asks about what first attracted me to the Ogdoadic tradition, what moves me in it, and what I find sacred in it. It is a difficult question to answer, because it has come to shape everything I think about the world. With the opening of the Citadel of the Caduceus here in London, I thought it might be helpful to attempt an answer.

Choosing – or being chosen?

One of the guilty secrets of western magic is that it doesn’t matter all that much where you get your basic training – as long as it’s good training. Mine, at what now seems a ludicrously young age, was in the general common magical framework of post-Golden Dawn ritual. It was with this background that I happened across a reprint of the first volume of The Magical Philosophy while browsing at Watkins. I can recall the sense of thunder dropping down my spine. I saw the kind of magical techniques I already knew, mixed with something else: love for the history of western magic, an immersion in ancient and renaissance Hermetic thought, clarity and ambition about magic’s purpose, a strong presence of the divine feminine, and a seriousness matched by emphasis on practical experiment. I loved its sense of literacy and love of culture. I sensed a living tradition radiating off the page. I soon picked up their Planetary Magick, too, and started to put it to work.

Much of what I love most in the tradition I sensed right at the beginning. Other things I came to grasp only later. It answered a need I had only half-understood. I loved the magicians and theurgists of late antiquity, their sense of a living cosmos knotted and crossed with desire and life; I loved the magi of the renaissance too, Ficino above all. I found the Masonic style of working cumbersome, yet valued the grace and power of ritual magic at its best. I found the tendency of many ‘respectable’ occultists to eschew proper magic altogether irritating; I also longed for the Gods. The tradition found fertile soil in me because I was longing for it. It was already at work in me.

A full magical autobiography would be tedious to recount. But I mention the above because, in retrospect, it’s sometimes hard to separate personal choice and being pulled towards a tradition by something deep inside. Causation seems circular. Synchronicities abound. Many practitioners have similar stories.

The Goddess

“Behold, Lucius, I am come, moved by your prayer, I, mother of all Nature and mistress of the elements, first-born of the ages and greatest of powers divine, queen of the dead, and queen of the immortals, all gods and goddesses in a single form…”

I love the tradition for the strong presence of the divine feminine. In the twentieth century a powerful impulse visible in mainstream and esoteric spirituality (as well as in art and literature) produced a turn to the divine feminine, usually in a creative synthesis of ancient tradition with personal revelation. Gerald Gardner’s devotional recreation of the witch-cult is only the most obvious example. Only our proximity to these movements prevents us seeing the wide sweep of divine influence in this remarkable change. Our tradition is no exception, and especially bears many traces of Melita Denning’s devotion to the Great Mother; its insistence on the sanctity of the body and nature come from the same impulse. (It is notable, and personally important to me, that the Aurum Solis and its successor orders were never prone to the homophobia and other bigotries common among old-school lodge magicians in the mid-to-late 20th century.)

Although much of our individual magical work centres around the Agathodaimon – the solar, theurgic initiator – Leukothea (lit. ‘White Goddess’) is of profound, even mystical, importance. It is She who brings forth the rays of the sun. She is called on as the ‘mystic grail, virgin of light and mother of ecstasy’; in one of our most beautiful workings the magician invokes her concluding: ‘Myrrha am I, and Marah am I, and Mem the Great Ocean. / Within me mingle Time and Eternity: / I am the Mother of all living, and I am the Womb of rebirth.’ Devotional praise ‘as her love-inspired and dedicated child’ and the total dedication of the work to her tutelary power are central to The Gnostic, one of the tradition’s core rites of spiritual elevation.

The Shape of the Sacred

I love the tradition’s sense of order and coherence. One of its key patterns, called ‘The House of Sacrifice’, is at once a way of understanding the interplay of divine forces, the dynamics of the individual magician’s psyche, and of structuring ritual work. As with the tradition’s approach to Qabalah, this sense of pattern is not flattening or artificially restrictive but generative. The House of Sacrifice is a pattern of great simplicity but infinite modulation, depth and refinement.

This sense of the shape of the sacred is tangible in its ritual work, which involves the creation of such a shape through the deliberate action of body and mind. Ritual actions always have meaning and purpose, nothing is superfluous. Elegant and classical, it is far from sombre. A grasp of its principles is profoundly freeing. When the shape of ritual is clearly understood, a great variety of tones and actions can be achieved effectively – from stark simplicity to abundant festal joy, from wordless invocatory dance to high conjuration.

Living Tradition

I love the tradition’s deep rootedness in the wider current of western esotericism. A synthesis of that current is presented throughout The Magical Philosophy, but it is most apparent in the ritual work. A broad framework inherited from the Victorian occult revival is streamlined and modified by Hermetic and Gnostic material, its Qabalah enriched and deepened, suffused with planetary and spirit magic of the grimoires. Twentieth century advances in understanding the mind – as well as the history of magic – are brought to bear on the work. It is, however, decidedly not eclectic: it is not buffeted by the winds of esoteric fashion, precisely because it knows the rewards of deep practice. At its heart burns a living flame; as a living tradition, its research and evolution continues.

It is a mystery tradition. That is, it prepares candidates for, imparts, and empowers them to transmit particular and profound spiritual experiences. Such experiences transform us in ways both hoped-for and unanticipated. The central theme of our mysteries is the Regeneration. As Denning and Phillips describe the Third Hall initiation: “He is gathered to the dim blue stillness of the vault; he hears the voice which placidly utters imperishable words, in even tones declaring changeless Truth as if no such thing as he had ever been; he is dissolved as if to naught; then, after silence, amid light and Memnon-cry of light’s triumph, he is drawn to his feet and forth.”

The Regeneration is a spiritual principle with many expressions and aspects. Our times – ecologically and socially, as much as spiritually – cry out for it. But if the phenomenon is in some measure universal, its form of transmission and manner of integration is particular – the wise fruit of long practice.

I love that I stand before my altar every day and place myself in a great chain of magicians ‘who were, and are, and are to come’. It is in their legacy and with the aid of those magical ancestors and discarnate powers that we work.

Hands-on Magic

I love that the tradition retains a strong place for practical magical work alongside works of spiritual development. This rectifies a disproportionate ‘spiritual’ emphasis in some traditions, which treats practical magic as grubby or vulgar. From relatively simple planetary rites to high-octane talismanic and Enochian spirit conjurations, the tradition provides many eminently practical methods for making change. It is not simperingly pious: it sees no contradiction between spiritual transformation and magic directed to concrete ends. Indeed, the one requires the other.

The Beloved

I love that the system centres on the encounter of the magician with The Beloved. Holy Daimon, Divine Friend, Higher Genius, Holy Guardian Angel: the name is various but the experience one. Tiphareth is the heart of all the worlds. All the magical training – from the alchemy of the Body of Light to the invocation of divine powers – prepares and empowers the magician to seek The Beloved, the primary quest of the new Adept. I love, here, the tradition’s emphasis on divine love, stressing that vision of the cosmos alive with love shared by ancient and renaissance magi before us. But I love, also, its emphasis on freedom, the recognition that the attainment of the Angel is unique for each magician and could not be otherwise. The point of our mysteries is not to churn out magical carbon copies, but to bring each individual into their own unique fullness and flourishing.

It follows from this that the tradition is a unity in diversity: it shares fundamental techniques, a corpus of ritual, and is centred around specific divine powers – and yet its realisation differs in emphasis for each magician. Just so, while the training ensures a broad familiarity with western magic and its practice, special concentrations call to the blossoming soul. One might feel the call to perfect the meditative subtle body work, or devotional god-form identification; another the formulae of spirit evocation or scrying the Olympic planetary powers. This diversity, managed well, is a great gift.

The Greatest Gift

Scholarship on ancient mystery cults stresses, these days, that they were specialised adjuncts to mainstream religion, not straight competitors or replacements. And yet the Mysteries they revealed were central to their initiates’ sense of the world and their purpose in it. Modern mystery traditions tend to articulate somewhat more complete worldviews and ethical frameworks than their ancient predecessors, though too much contemporary work on magic still adverts to basic technical discussion. I love the tradition’s integration of Jungian insight into its account of spiritual change, and the risks such change carries – as much as its high possibilities. (This is important: rapid spiritual change, and intense magical work, always carries a risk of psychic fracture and ego inflation . The art of integration is difficult and essential.) More, I love that it avoids the ‘psychologising’ trap that plagued so much of mid-century occultism while retaining its deep wisdom.

I love, and am thankful for, the gifts that the tradition has given me: a thorough grounding in magic, practical and spiritual; skill in meditation, and the wholeness of mind which arrives with it; powerful psychic, evocatory and magical experiences which filled-out, and altered, my view of the world; a healing rediscovery of inner joy, and joy in the natural world; ecstatic and mystical experience of divine powers; the experience of the world as a great theophany. The deepest, and most profound, gift the tradition has given me is a kind of metanoia – an inward turning of the soul towards the light. That sounds simple, and yet it is so far-reaching there is no area of my life it has not affected. I relish that there are more and deeper mysteries to discover.

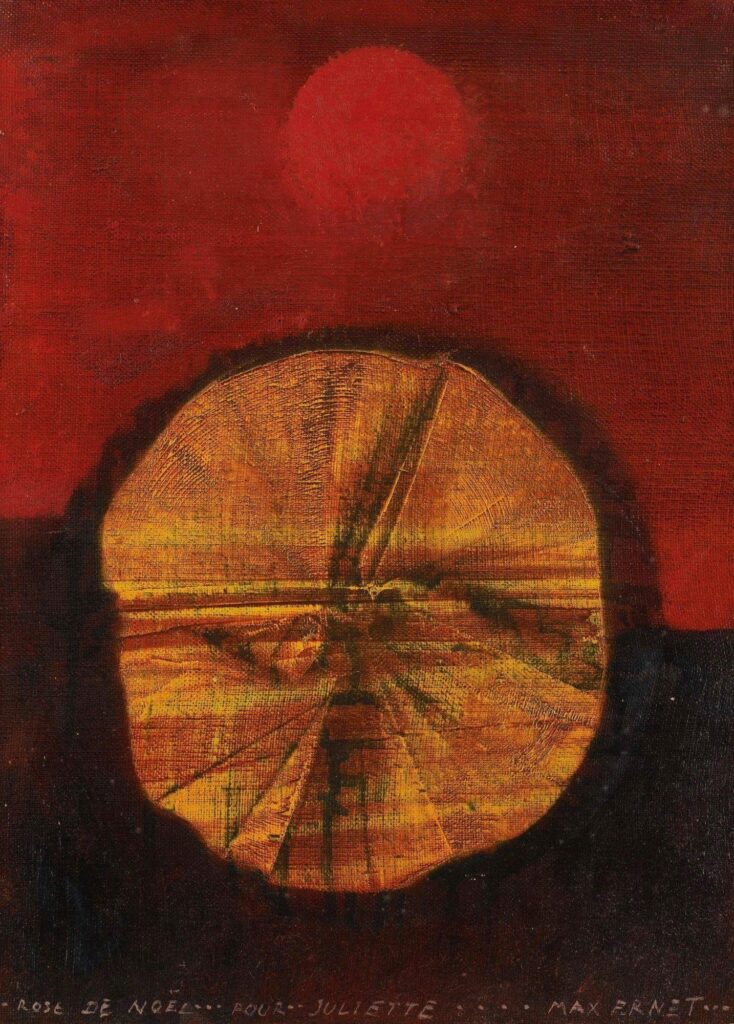

Above all, then: the gradual sense of the dawning inner sun, even the first rays of which work a deep, inner, alchemical transformation. This is no claim to perfection, nor even ‘advancement’, so much as a humble thanksgiving for a spiritual practice which has allowed me to become, in every sense, fully human.