Most students of the Ogdoadic tradition know that our primary texts – Denning & Phillips’ The Magical Philosophy – were initially published in five volumes, then republished in a combined and updated three volume edition. The differences between these editions are rarely explored, and are not, in themselves, important. But part of my training is in critical bibliography – the study of publication histories, textual differences, the physical qualities of books and manuscripts, and what they might tell us about the world in which they were made, and what their authors and publishers might have intended by them. So, naturally, I’m curious about the differences between these versions.

A caveat: those attracted to ritual magic, high magic and western occultism in general tend to be mildly bookish; as a specific body of learning, correspondences and spiritual technologies, magic falls under the sephirah Hod, the pre-eminent sphere of intellectual knowledge. But sometimes – and the internet does not really help with this – that book knowledge can turn arid, substituting the abstract and formal learning into a substitute for the living knowledge of magical practice. The qliphotic cohort attributed to Hod is the teraphim (תרפים), the idols: perhaps this suggests that this kind of book knowledge can all too easily become a paralysing substitute for real practice. Better the most tentative and humble honest attempt at magic than false wisdom derived only from books!

That said, there is plenty interesting in a comparison: while, for instance, the vast majority of material between the two editions is the same, the chapter on the initiatory structure of Aurum Solis is absent in the earlier volume. Were I taking a book historian’s approach, this new chapter between editions might be the most interesting: does it tell us that the authors just felt more comfortable talking openly about initiation rites, or does it suggest there had been some internal development and change to those rituals between editions?

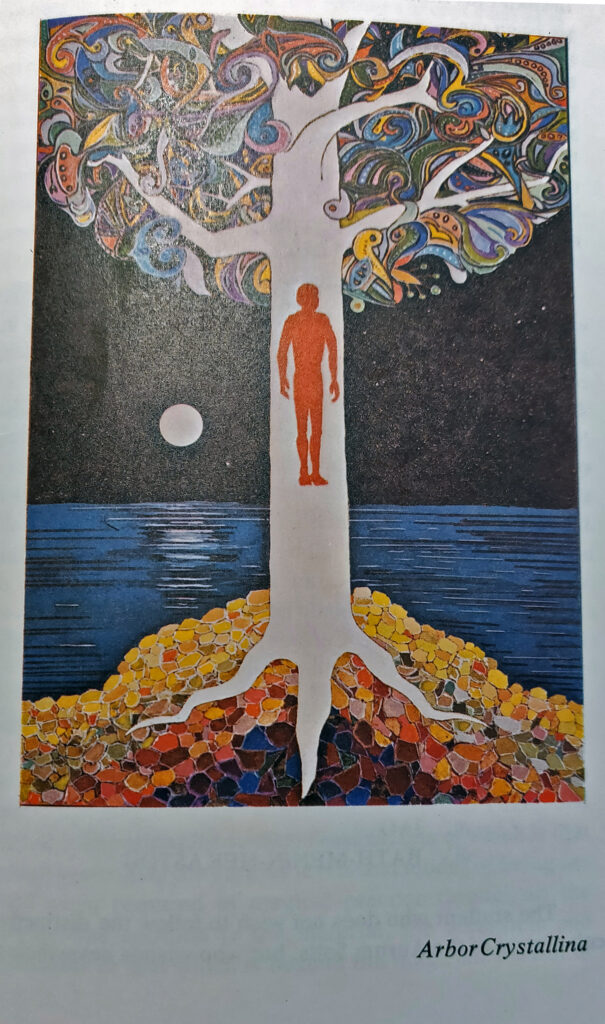

For the most part, the changes matter little, but I think it a little sad that the rather lovely illustration of the Arbor Crystallina didn’t make it to the second edition. Though definitely very 1970s in its execution, I think it rather better than some of the other illustrations mid-70s occult books had.

The image is accompanied by a Latin hymn-like invocation, which runs as follows:

Consistit columna in barathris

unde res occultæ donec prima ultima fiet non ostenderentur.

Sedem regiam qui ibi tenet ubi pendent inter ramos stellæ?

Silentes eæ gressus omnia invisæ decorant.

Ibi asylum, ibi umbrifera nox.

Ut in silvis immortalibus ibi innumera folia.

Ibi numen: ibi mortalitatis nihil unquam intus incolet.

Unus autem intus manit:

exornans matrem flamma.

With its translation given thus:

Established is the column in the depths,

whence secrets shall not be shown forth until the first becomes the last.

Who here holds the royal seat, where stars hang amid the branches?

She is not seen, but all things adorn her silent steps.

Here is sanctuary, here is shadowy night.

As in immortal forests, here are numberless leaves.

Here is divine presence: that which is mortal shall never dwell within.

But one is within:

Adorning the Mother is a Flame.

The context given suggests this evocative and mysterious invocation concerns the mystery of adepthood explored in The Triumph of Light, the relationship between the supernal powers and rational mind – and we might consider it an invocation of the primeval mother. Though quite sufficient on its own, the text is (I think) inspired by an ancient Akkadian hymn, CT 16 46. The hymn was translated by the 19th century philologist A.H. Sayce as part of a speculative essay on primordial Eden, the world-tree and the cult of Tammuz. The translation he gives is as follows:

1. (In) Eridu a stalk grew over-shadowing; in a holy place did it become green;

(A.H. Sayce, Lectures on the origin and growth of religion as illustrated by the religion of the ancient Babylonians, (London, 1888) p.238)

2. Its root ([sur]sum) was of white crystal which stretched toward the deep;

3. (Before) Ea was its course in Eridu, teeming with fertility;

4. Its seat was the (central) place of the earth;

5. its foliage (?) was the couch of Zikum (the primeval) mother.

6. Into the heart of its holy house which spread its shade like a forest hath no man entered.

7. (There is the home) of the mighty mother who passes across the sky.

8. (In) the midst of it was Tammuz.

9. (There is the shrine?) of the two gods.

There is much of interest here, but most striking is the image of the living Tammuz, burning like a flame in the crystal tree, the roots of which stretch to the primordial waters of Apsu, and whose branches cover the heavens. It is easy to see how this mytheme resonates with the account of magical development given in The Triumph of Light, with the dying and resurrected Tammuz, the living power of the sun, suspended in the primordial tree – the ruach united with the neshamah, the power especially attributed to the primordial mother. The A∴S∴ version of the hymn unites the symbol of the tree with the column, perhaps gesturing toward some of the foundational magical practices of the Ogdoadic tradition, many of which concern the activation (through meditation and ritual practice) of the central column within the body of the magician.

As an interesting addendum, Sayce gestures to a story told in an Arabic text, purporting to be a record of Babylonian practices, concerning Tammuz. It concerns the centrality of the dying-resurrected sun to the ancient mysteries. The same story is mentioned by Maimonides, in whose version it runs (with ‘images’ evidently referring to the pagan gods):

In that book the following story is also related: One of the idolatrous prophets, named Tammuz, called upon the king to worship the seven planets and the twelve constellations of the Zodiac: whereupon the king killed him in a dreadful manner. The night of his death the images from all parts of the land came together in the temple of Babylon which was devoted to the image of the Sun, the great golden image. This image, which was suspended between heaven and earth, came down into the midst of the temple, and surrounded by all other images commenced to mourn for Tammuz, and to relate what had befallen him. All other images cried and mourned the whole night; at dawn they flew away and returned to their temples in every corner of the earth. Hence the regular custom arose for the women to weep, lament, mourn, and cry for Tammuz on the first day of the month of Tammuz.

(Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed, cap. XXIX)