This is the second post in a series of ‘deep dives’ into the fundamental rituals of the Ogdoadic tradition. Find its predecessor here. These analyses are the product of practice and meditation on the forms, but they also draw on historical research and resonances within the wider magical tradition. Needless to say I don’t speak for the A∴S∴ or any of the post-A∴S∴ groups or orders: it’s all me. (And as such reflects my own idiosyncrasies and interests, which are wide but not universal.) This extended meditation will take us through the relation of magical force to the body, the work of the ancient Hermeticists, and the cultivation of the body of light – all latent in this simple little formula.

The Calyx has a claim to being the first properly magical ritual an aspirant practices – but because it is a simple little rite, it is often overlooked or subsumed into a broader discussion of the Setting of the Wards. But that would be to miss its potency. Its basic dynamic and symbolism are capable of significant elaboration – and it is intimately connected to some of the most powerful advanced work in the curriculum – but even by itself it is a powerful tool. Unlike the solar adorations, which connect the aspirant to the rhythm of the day and year (a useful sense to build ahead of learning planetary magic), the Calyx is magical: it draws divine force into the body of the magician with the intent to transform it. How? By breath, voice and image.

Breath and Body

In my last post I suggested that one of the hallmarks of magical techniques descended from the Victorian occult revival is an emphasis on visualisation, especially the visualisation of the body of the magician overlaid with concentrations of light or fire in symbolically important places, which vary slightly according to tradition – thus awakening powers or states of consciousness associated with this-or-that centre, or ‘charging’ the magician with the appropriate energy for a ritual. Of course this was partly the result of the revival of interest in esoteric yoga prompted by Bennett, Blavatsky et al, and really came to fruition through the popularising work of Israel Regardie –but there’s plenty of at least circumstantial evidence from the writings of late antique theurgists, some sections of the Graeco-Egyptian Magical Papyri and the more charming and disreputable parts of Late Platonism that such techniques were historically part of magical practice.

But my concern here isn’t really historical. It’s about what we do when we do ritual magic. One of the most attractive features of The Magical Philosophy, when I first read it, was the consistent emphasis on the physical body: from the careful attention to the basic gestures (and the flow between them), or the distinctive planetary gestures, and especially the stress on the ritual power of dance (which I know now to have been a deep love of Melita Denning’s.) This is good: one thing that has often puzzled me is the apparent neglect with which some magicians treat their physical bodies, or the odd, only half-inhabited relationship to the body some bring to ritual – self-conscious or half-hearted in gesture, shrunken in, afraid to properly grasp their own power. The body is the first and most powerful of tools.

Why might this be so? Sedentary lifestyles are part of it: serious magical practice helps break much of the appeal of screen-based life, but even then we moderns are historically aberrant in how little we move. In Don Kraig’s manual – still the first workbook for many would-be occultists – he recommends the ‘five Tibetans’ as part of daily work, but the details of the choice matter little. In truth, the issues go deeper than sedentarism – or rather, it’s the fruit of a more pernicious mind-body dualism set deep into our culture. Working away at that cultural pattern – taking the work of the body as seriously as we take the cultivation of the mind – is sometimes a tall order for ritual magicians, who are often by inclination bookish and retiring. It takes work and time to unlearn cultural patterns of disdain and neglect; in doing so you might learn how memories can lie hidden in muscle, or that what appears as instinct can reveal itself as conditioning. You might weep. But the rewards are many, because the body is the instrument through which we do our magic.

It is also the reason magicians are encouraged to learn their rituals by heart. The phrase itself is revealing: when we learn the words of a ritual – really learn them, not so that we can occasionally stumble through them but so that they flow from us like heat from a flame – we have made it part of ourselves. This is true in the trivial, physical sense of course: we’ve altered the material of our brains to hold the memories. It is also true in a magical sense: we can then allow the words to move us into gesture, or pay attention to the hum and resonance of the words in our body, the change they produce in the temple room. It is therefore also a kind of transubstantiation: dead words are given life through the body.

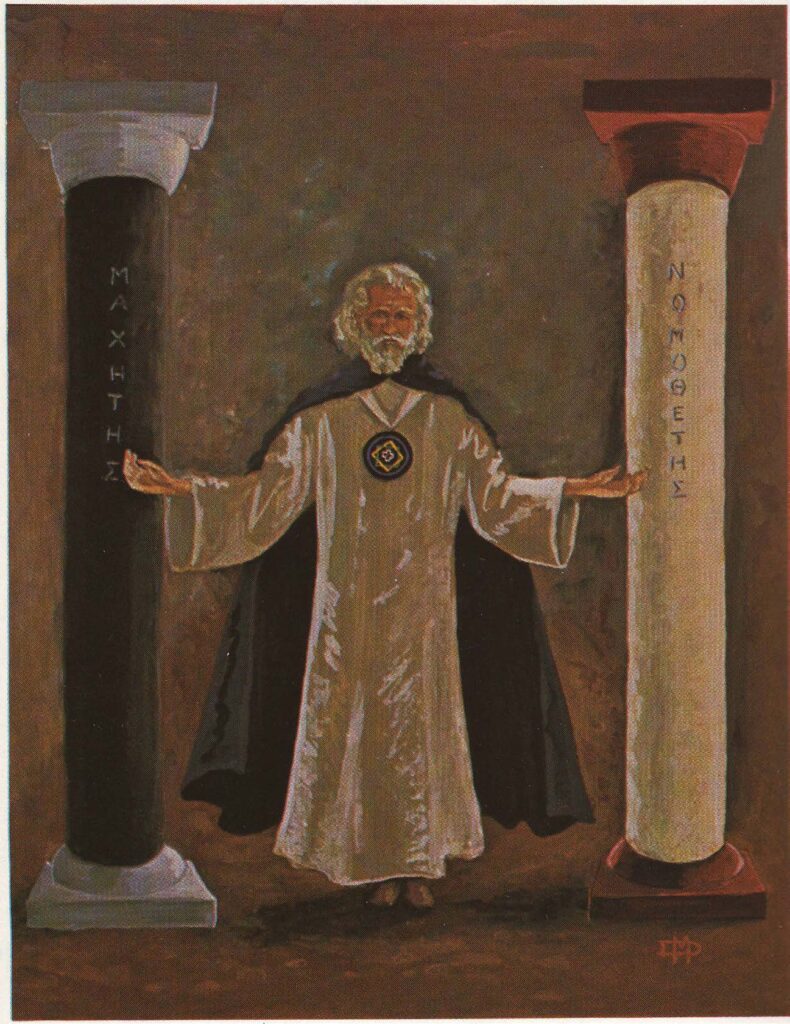

This may all seem like a digression in an essay purportedly about a very simple little rite. I am stressing it because breath and body are the key to unlocking these foundational practices. It is why, for instance, the study plan in the combined edition of Foundations instructs the aspirant to take a couple of weeks to really learn how to breathe, and even how to sit, stand and lie prone. (Just like the use of the robe and ring, these all become bodily cues that, combined with actual practice, become rapid ways of shifting one’s mind into the proper magical state, opening the senses, focusing the will.) Each of the foundational practices is carefully keyed to the breath, and so, when mastered, the visualisations and vibrated words should flow along with it. There is a reason that two of the names we give to the pillars of the temple are ‘breath’ and ‘body’: without them the temple cannot stand.

On Vibration

In many magical textbooks, instruction is given to ‘vibrate’ this-or-that magical name. Details beyond that are usually sketchy: effectively vibration is a form of chanting pitched in just such a way as to make the chest cavity resonate, with tingling physiological effects that can be felt throughout the body. Denning and Phillips provide a useful exercise in ‘finding the magical voice’ [TMP combined edition, I. pp. 295-6], which should help absolute beginners: once found it is easily relocated. Importantly, vibration is not shouting, bellowing or badly projecting the voice; many a novice magus has injured his (it is usually his) vocal cords this way, an injury which is not always immediately obvious. (There is, in fact, a place for shouting in ritual magic – as there is for most affective states. But it is rare.)

Is it just a physiological technique, then? No. Used correctly, it is the most tangible part of a magical action taking place on multiple levels, bringing the power of a given divine force into the body of the magician – and the temple space. This is why some magical traditions instruct students strictly to vibrate only divine names. It is hard to describe this technique without reaching for metaphorical language: I’ve just used metaphors of force and power, and a family of other metaphors about charge and energy are also frequently employed. Metaphors of music, tuning and resonance also help. I often find myself thinking of it like the physics of a lightning strike: building the small upward charge that creates a channel for the vast answering charge we thinking of as lightning proper. Fully developed – through familiarity with the physical technique and mastery of visualisation and concentration of the will – the effects of vibration can be brought about with very little noise at all. This is a matter of some relief when a magician might be staying in, say, a hotel room.

I spoke above of memorisation as a kind of small-scale transubstantiation; we can also think of vibration as a mode of deliberate magical transubstantiation, where the divine name is intentionally taken in to the body of the magician and allowed to transform it. Thus some authorities write of envisioning the name in white fire over the heart, or hearing the name resound to the ends of the universe. (This relatively simple technique can be elaborated into a system of mystical contemplation, prayer and ecstasy very similar to Orthodox hesychasm or Merkavah mysticism.) Thinking of it this way also lets us think about what should be vibrated and what not: what do you want to take into yourself? What power are you making way for, or bringing through your body? How central is it to the rite? And where does this leave us with the Calyx, which does not call for the vibration of divine names or nomina barbara, but a small formula, a magical doxology?

The Form

The text of the Calyx is available on the Citadel of Pharos’s website. For readers more familiar with the magic of the Golden Dawn, this is indeed very similar to the Qabalistic Cross. It invokes similar divine power – the same, in fact – from above to below, and distributes it in a symbolic balancing, ending at the heart centre; the Kabbalistic symbolism is the same, as are the words, save in Greek rather than Hebrew. Nothing to see here, then? The GD with the serial numbers filed off? Not quite.

The differences are small but meaningful. When presented in full, the Calyx comes with clear instructions for visualisation; the exact form of visualisation used in GD traditions varies slightly, partly as a result of never being clearly systematised in the order’s papers, at least in its earliest forms. (Very early adept papers don’t instruct on visualisation – see, e.g., Ayton’s copy of the pentagram rituals, now in the library of Freemason’s Hall – some claim this is a sign that it was communicated only orally.) Many recensions will instruct the practitioner to imagine growing to cosmic size, then to perform the cross by visualising three beams of light – following his gestures, one for each axis of space – to converge on his heart. The Calyx is similar, save that it lays greater stress on the descent of light from crown to feet: that invocatory movement, and its balancing, are the fundamental actions of the rite. Though the symbolism of the cross is present, in the Calyx it is secondary to the symbolism of the cup – which gives the rite its name.

It is my experience that such differences, though apparently small, can significantly change the feel and effect of a ritual. Why the difference? In general, where there are analogues with other forms of ritual magic, the version presented by Denning and Phillips is usually de-Christianised: that is certainly the case here. More substantially, the Calyx accords with the central symbolic structure of the Ogdoadic tradition – the House of Sacrifice [.pdf]. The drawing down of the light in its first two points (the major magical action of the rite) relates to the two pillars, the breath and the body; the subsequent three points represent the equilibration of that force through invocation of the triune superstructure. The emphasis is on the reception of divine force: properly achieved, the rite ends with the operator standing with arms crossed over the chest – in a symbolic position of resurrection and rectification – focused on the heart centre shining at the balance point of the microcosm.

There are already several threads to pull on there when thinking about the Calyx, then: the symbolism of the cup, the subtle motif of resurrection, the interplay of the breath and the body, the predominantly receptive and microcosmic orientation of the rite (i.e., the operator is doing something to himself), and the conclusion at the heart. All repay meditation. To dwell a little on the last: a fair accusation sometimes levelled at Anglo-American ritual magic traditions is that the solar focus of many of the initiatory orders, when improperly applied, can lead to ego inflation, narcissism and spiritual derangement. There is far too much evidence to deny this – many cases bearing similar hallmarks – and it is a serious risk especially for anyone writing, thinking about or teaching magic publicly. That so many orders now lay special stress on self-knowledge in their early training is one beneficial outcome: some work through analysis of the natal chart, others through exposure to a balanced variety of magical energies, usually the four elements. Personally I’ve found an exercise originally published by Norman Kraft useful: taking a six month chunk of your magical diary, use four coloured pencils to attribute elemental (or, properly, humoural) properties to the predominant moods across the period. This gives an excellent way into beginning the work of rectification and balancing. The Ogdoadic tradition is certainly not without its egos and public contretemps, but much of the ritual material demonstrates a special concern with keeping the operator well-balanced (for instance, the published pathworkings feature balancing rites for when they are employed out of sequence for magical purposes.) It is no surprise to find that feature in the Calyx, therefore: though it ends with a focus on the spiritual sun at the heart, there is a heavy accent on receiving, balancing and allowing oneself to be transformed by divine power. This rite, likely the rite a magician will perform most often through his life, is also especially a prayer – and can inspire humility alongside empowerment. It is a reminder, at the start of our work, every day, that the power we invoke does not come from us, is not the property of the ego, and is no more ours than the sunlight.

The Cup: From Hermes’s Vessel of Mind to The Grail

Why the symbol of the cup? On one level it is simple: the cup receives liquid as we receive divine power – it is a symbol of receptivity. It would be an excessive digression to spend many words disentangling the knot of spiritual paranoia, cultural dogma and genuine insight that led many magicians of a century or more ago to make dire warnings against ‘passivity’. Suffice to say the Calyx involves the active concentration of the mind and the will, and like all genuine invocation it can contain moments of weightless stillness and surrender to the current. Perhaps modern magic might be in a better state had those virtues been less scorned. Nonetheless,purely passive it is not: perhaps it makes greater sense to think of it as internally focused, especially when paired with the outwardly-directed ritual drama of exorcism and creation that constitutes the Wards.

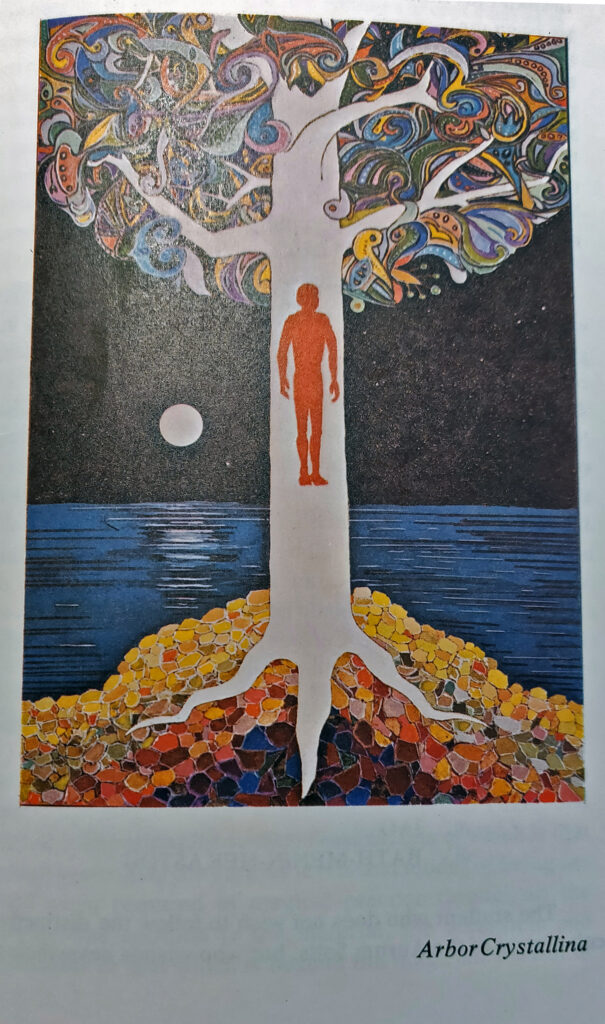

Yet it is more than a convenient symbol for the calling down of divine power. One of the less remarked but powerful features of ritual magic is that its fundamental symbols gradually unveil deeper layers over time. The motif of the cup will recur and deepen in the course of the work: this is not the elemental cup of water, but the greater cup, the grail.

The grail is a distinctive magical weapon used in the Ogdoadic tradition. Denning and Phillips say of it that though it “is not in one sense the ultimate instrument of the magician, [it] is the one used in the highest operations, for, being a symbol of the passive and receptive aspect of the Work, it may be used at those high levels where the magician cannot presume to command but only to situate himself so as to receive.” (TMP, combined edition, I. p.269) The consecration of the the Grail is one of the most beautiful of our consecrations, and there is much that may feed back into the practice of the Calyx from meditation on this ritual invocation of the ‘Virgin of Light and Mother of Ecstasy’, who declares herself thus:

‘Myrrha am I, and Marah am I, and Mem the Great Ocean

Within me mingle time and eternity:

I am the Mother of all living, and I am the womb of rebirth.’

The Calyx is not the Grail, of course, but I think it is right to see it as a prefiguration, and one of the ways the powers of the supernal mother are woven through the tradition.

The resonances of this cup are many, though: the protean object of medieval grail romance – at once stone of heaven, dish, or crown – or the regenerative, superabundant cauldrons of Welsh and Irish myth. Depending on background one might also hear chimes with the alchemical vessel, or the graal-work of many 20th century British occult orders, or even the Cup of Babalon of Thelemic mysticism. For me, though, most striking is the echo of ancient Hermetic texts, which speak of the krater full of mind. A krater is a large cup or bowl in which wine was mixed with water (or sometimes snow) before consumption; this social and domestic metaphor was given cosmic weight by Plato, who described the demiurge’s fashioning of the world-soul and human souls via mixture in a krater. Taken up by the Hermeticists, this becomes both an explanation of the different types of human souls in the world (a tripartite division is most common: divine, reasoning and those locked in the animal sense-circuit of stimulus and response) and the means of rising, freeing or divinising oneself. The texts sometimes seem to allude to a ritual drinking from the krater, and sometimes to a practice of immersion; a symbolic layering that has caused great confusion to scholars but will cause none to magicians. Its most prominent use is Corpus Hermeticum IV.4:

—κρατῆρα μέγαν πληρώσας τούτου κατέπεμψε, δοὺς κήρυκα, καὶ ἐκέλευσεν αὐτῷ κηρύξαι ταῖς τῶν ἀνθρώπων καρδίαις τάδε· βάπτισον σεαυτὴν ἡ δυναμένη εἰς τοῦτον τὸν κρατῆρα, ἡ πιστεύουσα ὅτι ἀνελεύσῃ πρὸς τὸν καταπέμψαντα τὸν κρατῆρα, ἡ γνωρίζουσα ἐπὶ τί γέγονας.

ὅσοι μὲν οὖν συνῆκαν τοῦ κηρύγματος καὶ ἐβαπτίσαντο τοῦ νοός, οὗτοι μετέσχον τῆς γνώσεως καὶ τέλειοι ἐγένοντο ἄνθρωποι, τὸν νοῦν δεξάμενοι·He [God] filled a great krater with it (i.e. mind, nous) and sent it down below, appointing a herald whom he commanded to make the following proclamation to human hearts: “Immerse yourself in the mixing bowl if your heart has the strength, if it believes you will rise up again to the one who sent the krater below, if it recognises the purpose of your coming to be.”

All those who heeded the proclamation and immersed themselves in mind [ebaptisanto tou noös] partook of knowledge [gnôseôs] and became perfect humans when they had received mind.

[tr. copenhaver, amended.]

There are many interesting features to this passage, including the divine initiator, the resolution and will of the candidate, and the emphasis on the heart – they are worthy of meditation. The text goes on to disparage those unable to understand the message, or those given over to the appetites of the world; it is one of the more ascetic and negative of the Hermetica. The theme was clearly thought central by ancient Hermeticists: Zosimos, father of Alchemy, makes pointed reference to it in his exhortation to Theosebia to plunge into the krater; his own visions contained a dramatic transformation in a vast altar-vessel. Recent scholarly attempts to reconstruct the initiatory practice behind the Hermetica have assigned this tract to an early, ascetic stage of the candidate’s progress, and its world-hating rhetoric is understood as specific to that stage – a preparation for the more exalted palingenesis [rebirth] of CH.XIII, in which Hermes hymns the presence of the divine throughout the material cosmos.

The cultural foibles of late antique Alexandria are not ours, and the confusion of the flesh with a prison has done much and enduring harm – especially when severed from that later vision of the god-breathed kosmos – but there is still great wisdom here. Given how often references to the krater are accompanied on the one hand by exhortations to self-knowledge and withdrawal into silence, and on the other contempt for the ways of the masses, I think modern scholarship is right to accord it an early position in the Hermetic way; the most perceptive scholars have also noticed that the symbolism transfers back and forth between the vessel full of mind and the candidate as a vessel to be cleansed before receiving divine power. Both valences are present at once in our ritual. (Similar exhortations to states of mental emptiness and receptivity are, as Eric Dodds noted decades ago, also present in the Chaldaean Oracles.) All this – for me – is hidden under the deceptively simple surface of the Calyx, a rite which I therefore regard as one that links me not only to my ancestor magicians who raised their hands every day in the same ritual, but further back to the Hermetic seekers and Gnostics of Alexandria plunging themselves into the well of mind.

What might the Hermetica teach us about the Calyx? It bolsters our sense that it is a rite of the reception of divine force, and one intended to transform the magician. The exhortations to practice self-knowledge, meditation or asceticism which appear in krater texts make intuitive sense as part of a foundational modern magical regimen. The disdain for the masses and the hierarchy of souls are less comfortable topics for modern sensibilities: without seeking to make ancient culture conform to our own, one sense in which this might be understood is as a description of the results of magical training. A consequence of repeated practice of the Calyx, alongside the other foundational rituals, is simply a greater awareness of – and control over – mental processes. Sometimes this can prompt a paranoiac reading of the world when one notices how many products and people seek to manipulate others’ psyches; more often it brings the candidate face-to-face with unpalatable truths about his own compulsions, self-excuses, or simply poor habits. It also frequently dims their attraction, and offers the possibility of stepping beyond them – if the magician is willing to embrace change. Given how much like death real change can appear, it’s hardly surprising that this often prompts the first serious crisis of the magician’s path. And from this position, it is easy to share the ascetic scorn of CH IV: all the more so in our age of new and more gleaming snares of the mind. But as the Hermetica also remind us: that’s not the whole story.

Two further small and useful points from our dip into the ancients. Where we instinctively reach for the word ‘energy’ to describe what we use in magic, we might equally reach for the ancient equivalent of ‘mind’ in the Hermetic sense. That is not to ‘psychologise’ magic, but to say that we live in a cosmos utterly permeated by noetic power, in infinite modulation and variety – and that we are part of it, and it part of us. This is the basis of our work. What is this mind? CH X.23 tells us οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ ἀγαθὸς δαίμων – ‘this [mind] is the Agathodaimon’, a figure of immediate interest to Ogdoadic magicians and other Hermeticists, and who will prompt a return to the Hermetica in a few posts’ time. The second point is this: though the word ‘calyx’ puts us in mind of the cup, the word has other harmonies as well, derived ultimately from καλύπτω, to conceal. Thus the calyx – the thick, green protecting leaves – conceal and protect the rose as it grows. The grail, too, is often depicted as a covered cup.

The Mirror of the Kosmos: Inner Alchemy and the Body of Light

You might very well ask, then, what is happening inside the calyx? Or what effect its repeated practice is supposed to have? Here is what Denning and Phillips say:

“As in all magical operations involving the central column energies, whether visualised as the downward-coursing light or as the Centers of Activity themselves, the primary domain of controlled function is the astrosome. Initially, therefore, the effect of such practices is likely to consist solely in the increase and harmonization of energy patterns within the astral body. But this is only the beginning of the process, for through continual and regular use of these practices, higher and more inward faculties of the psyche will become increasingly involved in the work, and a true harmony and interaction of forces will thus be wrought through all levels of the psyche.”

(TMP, III.9n.)

Note the emphasis – consistent through their work – that it is only repeated practice which allows the fullness of the rite to unfurl. There are two additional implications that are useful to note. First, the stress on the astral effects of the rite underscores the link between the explicitly magical works and the programme of mental training (meditation, scrying, astral projection) which make up the foundational work of the tradition. Regular invocation of divine force should and does aid in the opening of the subtle faculties. The second implication is that the Calyx is the first of a series of techniques that cleanse, fortify, open and empower the subtle body through the use of its central channel: most obviously this is true of the Rousing, a close equivalent to the Middle Pillar, but the same basic technique is modified into methods of rapid empowerment, projection, consecration and even invocation and assumption of god-forms. One development not outlined in TMP is into a form of healing, a method for which becomes obvious after some practice; the formula has also been developed into a method of sublimation and transformation of difficult or unwanted forces.

The Calyx is therefore the first step in a work of inner alchemy, one which awakens the microcosmic reflections of the powers and begins to move them towards equilibration. I will explore this inner alchemy more when we come to focus on the Rousing itself. Some of its effects have already been sketched above, so it is perhaps worth noting a few others. Increasing awareness of the way much of the world seeks to stimulate us (generally for profit or control) via our instincts is a particular instance of a more general sharpening of a sense of how our instincts work; one may also become aware of the way our thinking has bent to this or that dogma, that certain habits are not in our full control, or that one’s taste for various forms of passivity has diminished. It is also not uncommon to notice certain physical pains or tensions that that one had until now kept repressed and unconscious. Changing these is all to the good, though very public announcements of grand changes to one’s life (or The Great Reordering of The Universe, Shattering of the Aeons, Revelation of The Sole Mystic Truth) are best avoided, if only because these may in retrospect appear embarrassing. An undervalued power of the magician is silence.

The other result of unfogging one’s personal magic mirror is a greater sensitivity to people and places. Sometimes this manifests as auric perception, but sometimes as a clear and unmistakable gut feeling about individuals: inner discrimination ought to be ruthlessly applied to hone this faculty and free it of the dross of prejudice, because rightly used it is invaluable. The faculty extends beyond people to buildings and spaces; for magicians living in cities, especially, it can start as a strong and undefinable impulse to find greenery and nature, and it can be developed into an ability to properly feel the land (this can be, however, quite an overwhelming experience.) These effects perhaps underline the value of the Setting of the Wards of Power in ensuring the opening of this faculty is under our control, rather than the reverse.

On the Magical Use of the Calyx

All of the foregoing is taken from practice and reflection on this little rite: it is my belief that meditations and elaborations of this kind feed back powerfully into the ritual form. Perhaps that appetite for detail and history is no surprise, given my ascendant sits on the cusp between the first and second decan of Virgo. One Virgo quality, which can be set to use by the working magician, is a willingness to practice and perfect – but in its unbalanced form, that inclination to perfection can be paralysing and even disrupt the state of relaxed awareness needed for magical practice. (As a magician with lots of strong Air placements, too, it was the work of relaxation and letting go of the endlessly diffractive analytical mind which was by far the most difficult and rewarding lesson of early practice.) Though I think the magical use of scholarship – that is, reading serious work with a magician’s eyes as well as a scholar’s – is immensely useful for us, I would not want to give the impression that any of the foregoing is necessary to work or even to perfect the Calyx. It is simply one way of deepening the practice. I therefore conclude with these brief notes on practical applications.

First, Denning and Phillips’s comments on the rite: this ‘fundamental technique … aligns the practitioner with the forces of the cosmos and awakens awareness of the counterparts of those forces with the psyche.’ It thus encapsulates the ‘chief method and purpose’ of high magic. The formula is ‘variously employed as a psychic energiser, as a mode of adoration, or as a preparatory formula for the bringing through of power’ – they go on to highlight its use in the advanced formulae of transubstantiation or evocation as a gratulatio, a thanksgiving and a balancing at the end of magical work, and stress its use as a ‘complete “spiritual toner” in its own right” and commend its frequent use. Study of the advanced ritual formulae help develop this sketch: it is notable, for instance, that in work calling for the projection of force (as in a consecration) a different method is used, which draws power up as well as down the central column. These differences are not haphazard.

In my own practice, I have used the Calyx in most of the ways outlined above. That is to say, I usually use it as a prayer to begin and end the day; it combines well with the practice of solar adoration. I have also used it as an empowerment: obviously it is used as such daily in the Setting of the Wards, but personally I have also found it useful ahead of difficult mundane situations, or prior to events where I’m aware there is likely to be either conflict or hostility (here it is useful to conclude with a certain ‘hardening’ of the edge of the aura in visualisation.) Perhaps paradoxically, I have also found the Calyx useful in sensitisation – so I tend to use it prior to divination, or scrying, or when opening my senses to the land in a given place. (I should mention that it is also my experience that a well-performed Calyx might wake up presences which have been passive, resting or waiting.)

The form may also be developed into a slightly more sustained meditation than it currently is. The column of light may be sustained for several cycles of breath, arms extended, allowing awareness of the descending light – infinite, brilliant and unburning – to flood through the body, drawing to mind awareness of the twin powers of mercy and severity, warrior and lawgiver, on either side. After several cycles of this, the rest of the Calyx should proceed as normal, without further suspension, though some greater time may be spent in contemplation at its end. This simple expansion is – in my experience – quite powerful. It also brings us to a theme I will develop more fully in the future, but which is worth noting here: for this meditative expansion to work, the other practices of the central column – especially the rousing – need to be properly developed. With a little work, that is, the subtle body practices form a magical virtuous circle, in which they deepen and enrich each other, and reinforce each other’s power.

This tour around a very simple ritual has been extensive but not exhaustive: I hope it has given food for thought, and suggested that there are depths to be found in the contemplation and practice of even the simplest rites. In our next discussion, we will look at its use in a ritual of exorcism, which is also a miniature ritual drama of the creation itself –– The Setting of the Wards of Power.