Meditation is recommended by Denning and Phillips at various points in their work, but it is rarely emphasised as a foundational practice. This short addition to the Steps of the Foundation series of posts is a reflection on the role it has played for me in practice, and gathers some of the scattered references to meditation in the published Ogdoadic material. For the aspiring magician, meditation has three functions: one using the trained meditative mind to unfold and integrate texts and symbols; another, developing the skills of concentration, openness and focus needed in ritual magic; another, in ‘mystical’ meditation, a transformation and illumination of the spirit.

One word, many meanings

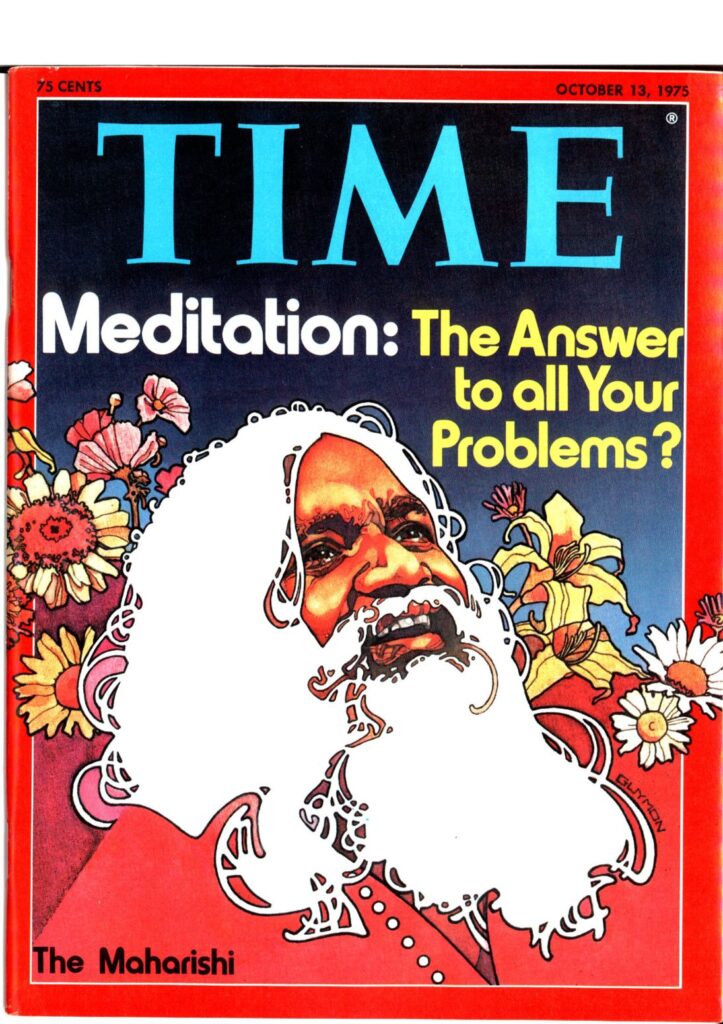

We should briefly think about the word ‘meditation’ itself, which can sometimes be an unhelpful one, summoning images of a saffron-clad monk turning his mind off, with the gentle chime of temple bells and a curling plume of incense. Successive generations of occult teachers bear responsibility for this, as they sought to supplement what they perceived as a badly degraded western tradition with techniques derived (sometimes badly mangled) from esoteric Buddhism. In fact, as we will return to later, sublime noetic silence is not unknown in the west: being ‘alone with the alone’ was greatly desired by later Platonists and their inheritors. But an emphasis on total mental silence misrepresents the range of meditative practices in Indian and Tibetan sources, and obscures the shades of meaning the word possessed in European thought. In Crowley’s system, responsible for much of this overemphasis in 20th century magical culture, it is combined with a range of pointless if characteristic exercises in sadism. The aim in elementary meditative practices is not to achieve non-thought, but to concentrate one’s thought and attention – with minimal deviation or wandering – on an object, principle, symbol, or to achieve (as far as possible) mental dwelling purely in the single present moment. These are achievable goals. The ability to return at will to this ‘still point of the turning world’ is a very helpful one in magic.

In the long span of European spiritual thought, ‘meditation’ usually meant bringing the mind to bear on an appropriate object. Some Stoics, certainly, knew something like it; Christian scriptural devotion works in a similar way. The form of mental attention intended is not excessively rational, nor the mental recitation of material got by rote – involving instead a calm pursuit of chains of association, allowing the intuition to descend and guide the reflection. (To use the jargon of western magic, the desire is that the ruach is guided by the neshamah.) In appendices to each volume in the first edition of The Magical Philosophy, Denning and Phillips give a series of exercises using flashing tablets as a means of developing this skill; these exercises are condensed into a single brief reference in the combined edition’s guide to practice. They recommend the absolute beginner construct tablets for Jupiter and Mars, and meditate on these for a week each, in succession. (Note here the very strong emphasis, very early on, on balance between the powers, a theme repeated through the Aurum Solis material.) The exercise can be repeated for all seven planetary powers, and then go well beyond them. I have conducted sequences of meditations on traditional magical images, the Major Arcana (fairly regularly), as well as texts – including ritual speeches, but also highly allusive alchemical texts and passages of the Corpus Hermeticum.

This form of meditation, sometimes called discursive meditation by modern magicians, is a great boon. Some distinctions ought perhaps to be made: direct meditation on a power, though not an invocation itself, will bring some kind of contact with it. It is not unusual to feel one’s concentration ‘picked up’ and recognised by that power – the feeling is unmistakable though difficult to describe, and can come with an overwhelming jolt of emotion or mental disposition suitable to that power. Sometimes one feels a symbol unfolding itself to the mind: thus some magical groups give students specific symbolic meditations to foster deeper connection with its egregore. Defects in mental attention are more noticeable and more easily corrected than when trying to silence the mind altogether; love for the ever-creative perceiving mind and a gentle but unswerving return to the object will develop the skill much more securely than brutalising the body.

There is, however, another form of meditation in western spiritual traditions, strikingly similar to some yogic practices. This is the use of certain psycho-spiritual techniques – visualisation, repetition of divine names or prayers, withdrawal from the senses – to encounter the divine light. This mystical, or contemplative, form of meditation seems to have been discovered and rediscovered – or transmitted – among diverse spiritual traditions, often upsetting more conventionally religious practitioners whenever it broke out. The Aurum Solis technique of ‘Rising on the Planes’, given in a little-discussed section of Mysteria Magica, may produce an analogous effect. But one of the most potent forms of this meditation was publicly outlined in one of Denning and Phillips’s mass-market New Age paperbacks – effectively powerful little bits of occultism dressed up in voguish ‘80s pop jargon. They called it, with a nod to its origins, the Tabor Formulation. We will return to this crucial form of meditation below.

Two further points on the question of ‘East’ and ‘West’. There has long been a scholarly movement questioning the usefulness of the ‘western’ in ‘western esotericism’. Certainly in a time when all sorts of claptrap about innate ethnic spiritual traditions gets smuggled in under the name of esotericism, it is useful to stress that esoteric thinkers in the west have often looked to sources they perceived as older and outside their culture for wisdom – Chaldaeans, Arabs, Indians or Tibetans. If it is still cogent to talk about western esotericism – and I think it is – then it is a tradition that is highly porous, often hungry for wisdom from elsewhere and just as often disclaiming the sources of that wisdom.

On that note, though, I believe there are great benefits for magicians in engaging in some of the basic Indian and Tibetan meditative techniques which have made their way to the west. So-called ‘shamatha’ or ‘shinay’ technique – sometimes called ‘calm abiding’ – is a superb foundation for any meditative exercise discussed here. Many of the Buddhist centres in Europe and the US teach introductory classes in (putatively) non-denominational formats; one London centre has a decent pair of recordings online.

But why meditate?

At the outset I suggested that meditation is an essential foundation for (this kind of) magic. Most of the reasons I gave were instrumental, e.g., that developing mental direction and focus is essential for invocation. That is, meditation is important because it allows us to do something else. This is of a piece with the graded curriculum-style approach to magical training taken by most older magical orders, which build up by deepening and expanding a set of fundamental ritual practices. They’re also structured according to certain magical-experiential landmarks, which simply recognise that – in general – repeated practice brings on experiences which, while individualised, are predictable and recurrent. My quibbles with this style of instruction aside – that it would benefit from incorporating some of the last century’s advances in pedagogy, and disliking its infinite capacity to inspire stupid competitions about ‘rank’ – it is a better start to magical practice than the consumerist pick-’n’-mix approach common today, partly because it should decentre the instincts towards consumption and immediate gratification on which much of contemporary society is based.

Meditation also has benefits in its own right. Among them is the capacity to recognise the way the individual mind moves, exercise control over it, direct it, still it or open it. It can grant awareness of the emotional manipulation common in advertising or mass media. And it can grant insight – sometimes initially painful and unwelcome – into the emotional and mental burdens, often unconscious, which pattern and sometimes warp our lives. These are especially helpful in the world of occultism, where many seekers who wash up on its shores do so injured and ill-treated, suffering and harming in turn. This is not a sneer: the world is a frequently cruel place, and often specially cruel to those who feel the yearning for spirit. Few make it into adulthood without carrying some such burden; modern occulture tends, perversely, to reward people who feign having overcome all such problems, and discourages its prominent names from talking honestly about them. The cyclically-repeating dramas which periodically tear through public-facing occultism look, with a little distance, like symptoms of just such problems. The powers of discrimination, self-possession and insight granted by meditation are significant remedies for these afflictions; I know some candidates for whom these meditative gifts turned out to be everything they needed from their initial attraction to magic, utterly transformative in themselves. They are essential for all of us, especially solitary magicians – not least in interactions with the wider occult ‘scene’, where capacity for discrimination is essential.

There is a wider point here. Denning and Phillips often write that magic is a way of freedom. That is true, and it is also a good test: if a particular practice makes one feel less free, more fearful or diminished, or a tradition demands unthinking loyalty and open wallets, then it’s probably harmful. There are nuances: sometimes binding ourselves to a discipline might make us more free, or we might give up our freedom to speak about certain things as a sign of respect and trust – but in both cases the sense ought to be that such commitments enhance, rather than diminish, our sense of agency. Freedom, however, is not always easy: the corollary of increasing agency and freedom is increasing responsibility for one’s decisions, a prospect which can initially be terrifying. But magic, even in its most highly spiritualised form, has always concerned itself with liberating the practitioner from powers which predetermine or constrain his or her life – sometimes understood as the disposition of the birth chart – and remedying their afflictions. Thus Ficino, in whom Saturn’s black flowed strongly, hung his neck with gold and danced in a secret place to the Sun.

It might be objected that none of this is magic proper, but a combination of psychological self-examination, spiritual exercise and self-improvement. Quite so. The theurgy taught in the Ogdoadic tradition combines spiritual transformation with its practical magic, a combination which recognises that one informs the other – and that combination is as ancient and venerable as disciplines which focus solely on either meditation or spirit-calling. (I stress this point because there has been much bad-tempered polemic on the issue in recent years.) The tradition also avoids the habit of some more staid schools, which insist on many years of meditative practice before engaging in practical magic at all, preferring to allow the one to develop alongside the other, thus intentionally speeding up the transformation. The speed of this transformation makes a strong meditative practice desirable: would you build a temple on shifting sand? If the personal insights and gradual transformation gained from meditation – discursive, contemplative, ‘calm abiding’ – seem less magical than the power of scrying, spirit invocation or talismanic consecration, that is fair. But it is worth stressing that almost all magical traditions incorporate such work of rectification into their earliest stages – whether elemental initiations, first degree, first hall, pronaos. To repeat: there are few skills as important and transformative as the ability to anchor oneself to the still point of the turning world.

The Uncreated Light

As Denning and Phillips give it, the Tabor Formulation proceeds very simply thus:

Stage One: Simple Breathing – Lower your gaze, fixing it upon your navel or a point in that region. Breathe in an even, gentle manner as deeply as you can without strain. If your mind wanders, as soon as you notice bring it back gently but firmly to your breathing.

Stage Two: Awareness of the Light – Entering into the second stage of the meditation, on an in-breath be aware of a nebulous radiation of golden light, which is also a radiation of love, from just below your sternum; it seems to form a luminous cloud about midway between your navel (at which you continue to gaze down) and your chin.

You don’t have to do anything about that light. Simply be aware of it, of being illuminated by it, of being loved by it. Accept that awareness; don’t think about it, don’t even try to aspire to it. Just keep on being conscious of it, and of your breathing.

Stage Three: Silent Utterance – Retaining awareness of your breathing and of the light, silently “utter” mantrams – phrases or single words – which you feel to be suited to your meditation: formulate each word distinctly in your mind, but with no vocalization or movement of the mouth. You will need two mantrams to use together, one for the in-breath and one for the out-breath. Their chief purpose is to express in brief compass something of your essential relationship with the Cosmos. It is to affirm your bond of oneness with the Cosmos: that bond in which you are sustained by the beneficence of the Whole, at the same time participating actively in the Whole. You are a living and purposing component of it, giving forth again with blessing that which you receive.

We’ll return to the question of what phrase to use below. Two very brief notes on this technique: the next post in this series will take in the Ogdoadic tradition’s method of awakening the centres, but here it’s worth noting that the solar plexus centre is distinct from the heart centre proper. It is used in psychic operations, like the formation of the astral double, but not included in the standard (middle pillar-like) rousing of the centres. That the light is first experienced through the emotional and instinctive nature governed by this centre, rather than the higher rational faculties, may chime with the chapters on the Holy Guardian Angel in Book IV of The Magical Philosophy.

Students of Christian mysticism will immediately notice the source of this technique: Hesychasm. Derived from the word ἡσυχία, meaning ‘stillness’, this internally-directed form of prayer involved psycho-spiritual techniques similar to those used by modern occultists. It flourished among Athonite monks, who silently recited the Jesus Prayer while gazing downwards, thus mocked by opponents of Hesychasm as navel-gazers. The light experienced by advanced practitioners was interpreted by Gregory Palamas as the ‘uncreated light’ seen on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration. (Those interested in the occult uses of music may find it suggestive that the drone in Byzantine chant – the ison – is taken to represent the Tabor Light.) The Greek Orthodox compilation of mystical theology, the Philokalia, has extensive reflections on this practice, especially in its fourth and fifth volumes. Here it is shorn of its Christian trappings and non-denominationally ‘universalised’.

A Hermetic Hesychasm?

This might give the conscientious modern magician pause. Many of us are less confident than our predecessors that the inner technology of a method can be so easily separated from its given cultural form. Even if Christ and the Agathodaimon, for instance, are two expressions of the same solar mystery, is the ritual repertoire for one so easily transferred to the other? (In this case, at least, many ancient Orthodox writers are happy to talk about the psycho-spiritual technique as distinct from its prayerful content and orientation; this, of course, they see as a danger.) Other problems arise: the states we seek using this technique, and the manner in which we use it, are precisely those about which Orthodox thinkers are at best ambivalent – in fact, many of them would think it dangerous, irreligious and disordered. But in too ready a rejection of a thousand years of writing on this form of meditation, we risk losing some of the wisdom which can enhance our practice.

I don’t worry so much about the magpie nature of modern magic, though I try not to be an ass about it. Hermes is also the god of thieves. I am especially relaxed about adapting this practice, because I believe very similar techniques are likely to have been used by non-Christian mystics throughout the Mediterranean basin in late antiquity. The parallel is often drawn between the posture adopted by Jewish mystics ‘going down’ to the Merkava and the Hesychast gaze, but something similar is at play in Plotinian spiritual exercises as well as later Iamblichean theurgic technique. I am also absolutely certain that a similar method was used by ancient Hermetists. Consider the famous opening of the first tract of the Corpus Hermeticum, where the speaker enters a state similar to sleep, κατασχεθεισῶν μου τῶν σωματικῶν αἰσθήσεων, ‘my bodily senses suppressed’: an emphasis on withdrawal from the bodily senses also characterises early Hesychast writing. It is through this withdrawal from the outer senses that Hermes encounters a vision of limitless divine light and its shepherding mind (ὁρῶ θέαν ἀόριστον, φῶς δὲ πάντα γεγενημένα – C.H. I.4). That tract was certainly supposed to inspire recognition in its readers of meditative techniques they themselves used.

A little thought along these lines will be enough to dispel the notion that meditation is an alien graft on to western magic. In its discursive form, it was so common a spiritual practice as to be unremarkable for most of the last millennium; in its contemplative form it is recognisable in the pagan desire for henosis – union with The One – and in precious traces in hermetic and theurgic texts. It is recognisable in mystical traditions in Eastern and Western churches, though often condemned by their official authorities. Though there are certainly forms of magic which can be done without it – ecstatic forms of witchcraft, natural magic – meditation, in at least its discursive form, is a key foundation stone for modern ritual magic.

Of Words and Warnings

Discursive meditation is best brought to perfection by doing; the rest of this note focuses on contemplative meditation of the Tabor Formulation type. Denning and Phillips recommend choosing a short phrase or mantra to accompany the rhythm of the breath, and give examples: ‘Light and life fill me / I share my abundance with all’, or ‘Energy / Ecstasy!’ Both are fine as they go, though their New Age formulations now seem a little dated, and of course they would horrify an Athonite monk.

It’s always fun to horrify a monk, however hypothetical, but there might be something worth listening to as well. Hesychasts utter the Jesus prayer because their meditation is precisely that, a form of prayer. However strongly we dislike the prayer’s pleading for mercy and repeated self-identification as ‘a sinner’, it does stress the partiality and finitude of the individual – that divine presence is an act of grace, not a mark of personal power or election to sainthood. One need not share Christianity’s theology of grace to see there is something important in its emphasis on inwardly-directed humility, especially as a guard against spiritual delusion. There are two way to incorporate this insight into practice: one is to formulate the phrase more clearly as a prayer – perhaps taking inspiration from the various hymns in the Hermetica (especially CH I and XIII). Another is, simply, to adopt a humbler, more reverent attitude: not of cringing self-abasement, which is just the shadow of self-importance, but the calm joy which can come from participation in the light.

Personally, my experience of this kind of meditation includes a sense that one’s own intellectual structures are clumsy approximations of the real, a sense almost like being a little brother marvelling at an older, infinitely more complex, loving and wiser mind. So different, in fact, that even the word ‘mind’ isn’t right for it, and my phrasing here is only a partial, sublunary approximation. It’s no accident that the verb for seeing used in the Poimandres – θεάομαι – refers to a different, visionary kind of seeing; it is also the verb Plato uses for the sight of those who have left the shadow-world of the cave.

For practitioners who work with the divine powers of the Ogdoadic tradition, orienting this practice to the Agathodaimon is another potent option. A future essay will discuss the Agathodaimon more fully, but it suffices here to say that he is the solar theurgic deity par excellence, and utterly fitting for invocation in this practice. The two phrases I have used in this practice are the god’s name – ‘Knouphis / Agathodaimon’ – on in- and out-breaths, and a paired epithet derived from the wider tradition: ‘who comes forth as the phoenix / who shines as the morning star’.

Wash the Dishes, Sweep the Floor

Meditation is not magic, though it is an immensely helpful foundation for magical work. Mystical meditation of this kind should form part of a magical routine, rather than replacing it entirely. Many classic occult authors warn against merely seeking absorption in the infinite; one of the most desirable magical skills is the development, from long practice, of the ‘Janus-faced’ position of the soul, pointing both inward and outward at once. Denning and Phillips borrow that phrase from one of Ficino’s most touching letters, and though it is a skill few of us will master as a permanent state it is a key to unlocking deeper levels of practice. They were more circumspect about drawing from the treasury of writing on Hesychasm, doubtless ambivalent about its ascetic Christian disposition, there are two points from the literature useful to us.

Many Hesychasts write at length about the danger of spiritual delusion; many of them would categorise everything we do under exactly that category, if not demonic obsession. Nonetheless there are insights to be gleaned from the extensive writings on πλάνη (planê, lit. wandering), or spiritual delusion. In particular, these case studies stress cases where people have received flattering visions or intensified their spiritual regimen and begun to think of themselves as special, saintly or prophet-like. Anyone who has watched an occult group fall apart because of inflated egos or delusions of singularity will recognise these symptoms (which are sometimes associated with excessive invocation of Solar powers.) The remedy prescribed in the monastic tradition is usually a grounding, earthly kind of humility: sweeping the floors, washing the dishes, digging the garden. It’s an insightful remedy, placing us back in the body, a human among other humans.

One sign of incipient planê among occultists is an excessive intensification of the daily regime, to the detriment of other aspects of personal life. Its remedy is two-fold: first, the adoption of some volunteering work which actively benefits the living world and, ideally, exerts the body. That might be soup kitchen volunteering, given the number of homeless in our great cities, or active restoration of the natural world, given how important our changing climate is. Involvement in political movements around these issues is also an option, though many of the same risks of ego inflation attend that arena; a good remedy to that is absorption in the tiresome, dutiful service part of political work. The second aspect is the development of a strong practice of discursive meditation, through which any visions or revelations ought to be integrated into the waking mind – with detachment and compassion, understanding the powerful but personal and subjective symbols with which the living cosmos communicates.

The Philokalia lays great emphasis on the spiritual director or confessor, in the same way that many Tantric texts lay emphasis on the guru (this is not the only point of striking similarity between these two spiritual traditions – a subject for another time.) Even within traditional magical orders today such a close supervisorial relationship is rare, although admirably more common than it used to be a couple of decades ago. The practice of the magical diary, and regular examination of its entries to discover recurrent themes and patterns, partially remedies this absence – provided it is filled in honestly. Nonetheless, the decrease in serious ‘communities of practice’ means that the individual magician often has to bootstrap their own development, sometimes without trusted friends to check in with: the internet has, as ever, proven a double-edged sword in this regard. As I get a little older, I am struck by how much I return to the question of community and its relation to spiritual practice, and how surprisingly little many occultists have to say about it.

The Hesychast literature also outlines three stages of the mystical life: purification (κάθαρσις, katharsis), contemplation (θεωρία, theoria), and divinisation (θέωσις, theosis). This division is very ancient indeed, and goes back at least to Pseudo-Dionysius; the latter two stages are sometimes also called illumination (φωτισμός, photismos) and perfection (τελείωσις, teleiosis). Some later writers are keen to stress that progress between them is not linear, as if they can be checked off and forgotten, attained for all time. But initiates of many western magical traditions will recognise a common structure here: the First, Second and Third Hall initiations of the Aurum Solis and its descendant orders can be seen to map, though imperfectly, to these stages. The same, naturally, can be said of the magical work of the sefirot of the middle pillar in ascending order. Though by no means is all of it applicable, much of the literature on these stages can provide precious insight to an often neglected aspect of western occultism. It is perhaps worth noting in conclusion that the sole active inner body of the Aurum Solis before Osborne Phillips relinquished his role as grand master was explicitly oriented to the practice of theosis.

The next post in this series will return to our foundational ritual practices, with an examination of the practice of the light-body, the Clavis Rei Primae – which, in truth, sits somewhere between meditation and ritual. When I finish a session of Tabor meditation, I typically close with this adoration derived from the Hermetica, and so I do here:

O Powers within me,

hymn the One and All:

chant in harmony with my will,

all ye Powers within me!

Holy Gnosis, illumined by thee,

through thee I hymn the light of thought,

I rejoice in the joy of the mind.

All ye Powers, chant with me!